Chapter by:

Jaleigh Q. Pier, Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York

This chapter was first publicly shared on October 25, 2019.

Chapter citation:

J.Q. Pier. 2019. Brachiopoda. In: The Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life. https://digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/brachiopoda

Chapter contents:

1.Brachiopoda ←

–– 1.1 Brachiopod Classification

–– 1.2 Brachiopods vs. Bivalves

–– 1.3 Brachiopod Paleoecology

–– 1.4 Brachiopod Preservation

Associated materials:

Virtual Teaching Collection of 3D photogrammetry models of brachiopod fossils.

Above image: Fossil brachiopod specimens from the collection at the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca NY. Image by Jaleigh Q. Pier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Phylum Brachiopoda Snapshot

- Living species: ~350

- Extinct species: ~12,000

- Ecology: marine (ocean) filter feeders

- Key features of group: two unequal shell halves (valves), lophophore feeding organ

- Fossil Record: Cambrian-Recent

Overview

Brachiopods are marine invertebrates, meaning they have no backbone, and are one of the few animal groups that live only in the ocean. They live on the ocean bottom in a variety of places, including soft sediments, on rocks, reefs, or in rock crevices where some even anchor themselves with a muscular stalk called a pedicle. To eat they filter particles and detritus (dead organic matter) out of the water with a unique feeding organ called a lophophore. Although they have hard shells with two halves (valves), they are not related to clams (bivalves). Read the Brachiopod vs. Bivalve page to learn more about differences between the two groups.

The name ‘Brachiopoda’ comes from the Greek words ‘brachion’ (=arm) and ‘podos’ (=foot). They are sometimes referred to as ‘lamp shells’ since certain groups, mainly the terebratulid brachiopods, resemble ancient Roman oil lamps.

Brachiopods have been around since the Cambrian (~550 million years ago) and were among the first animal groups to diversify on Earth. During the Paleozoic era (541-252 million years ago) they were the most common shelled marine macroinvertebrates. Although brachiopods are still around today, their diversity has greatly diminished compared to their heyday during the Paleozoic. They now typically inhabit colder and deeper marine environments and are no longer common constituents of warm, shallow marine habitats.

Some groups like the lingulids have changed very little in shape over the last 500 million years. This is why some brachiopods are referred to as living fossils. Visit our Virtual Exhibit on living fossils to learn more!

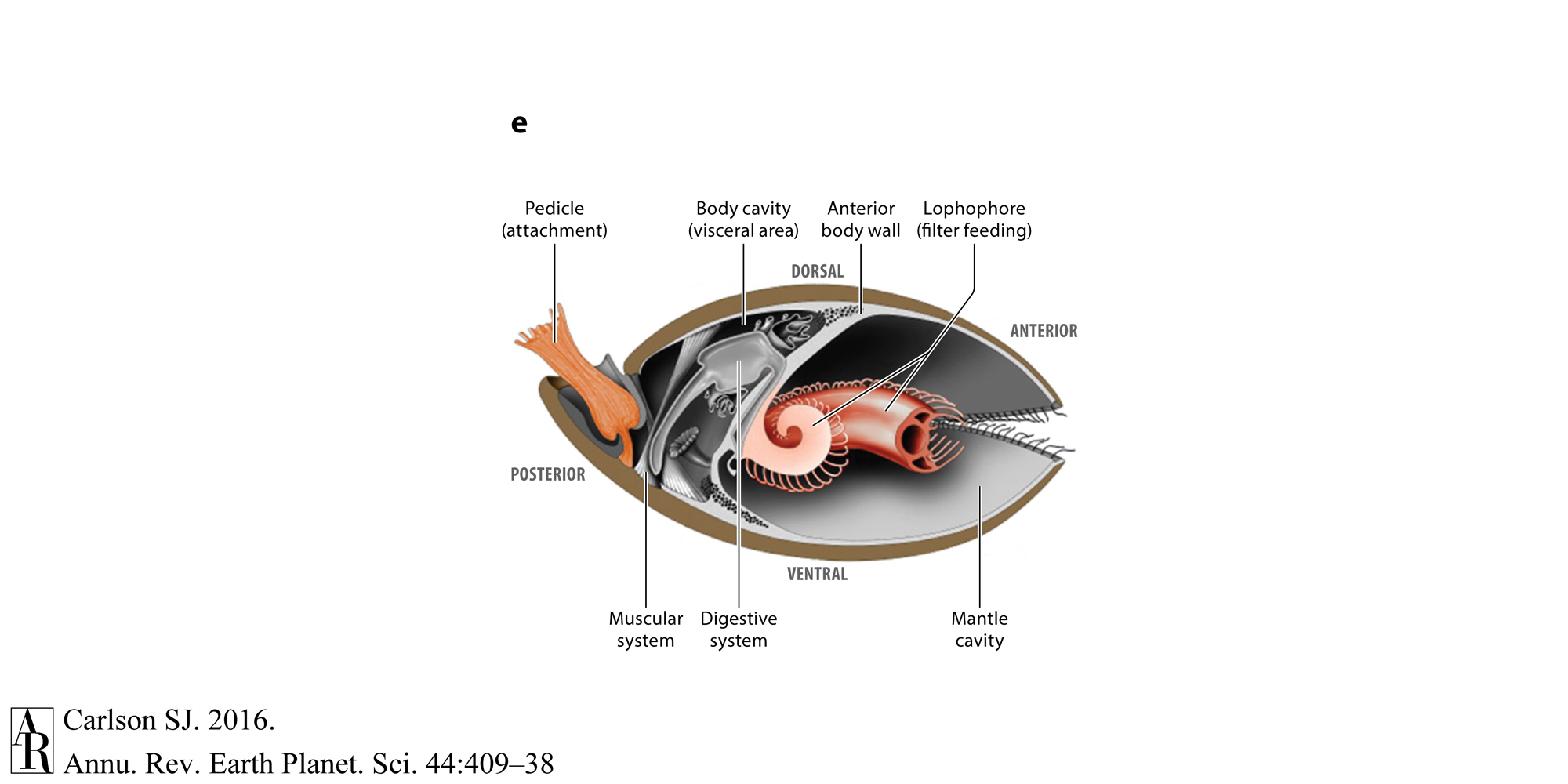

General Features of Brachiopod Shells:

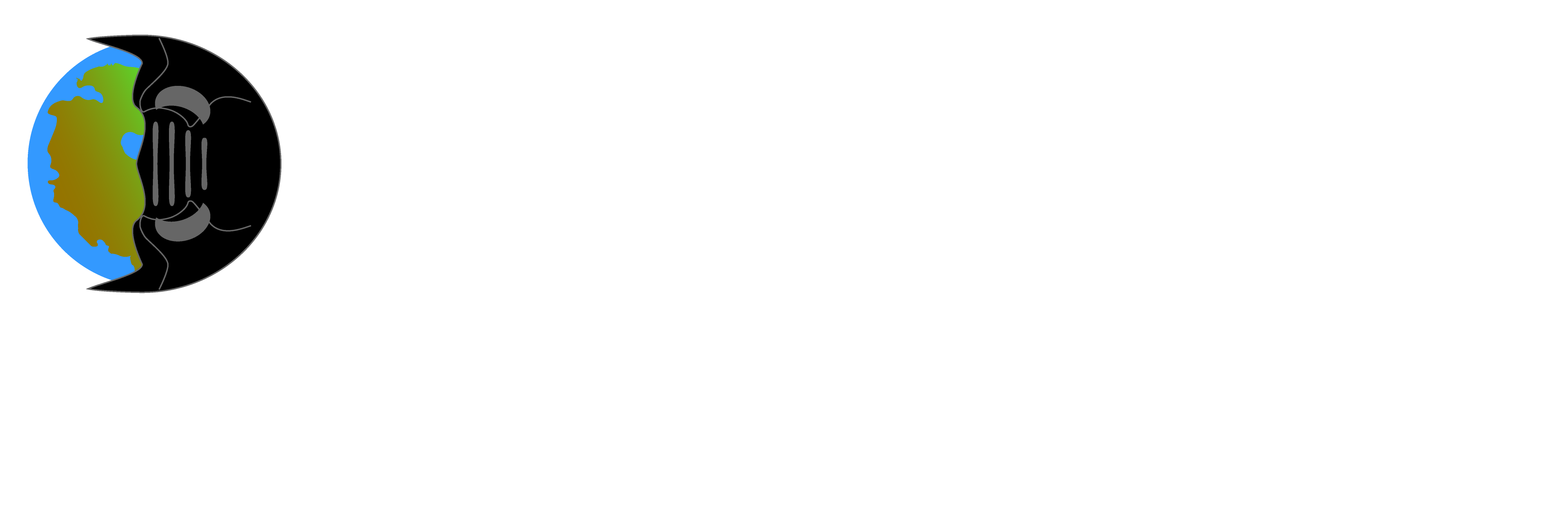

Brachiopod shells have two valves that are distinct in shape and size. The brachial valve is usually the smaller of the two valves and has supports on the inside to help support the lophophore. The pedicle valve is usually larger than the branchial valve and has a hole through which the pedicle passes (the pedicle foramen; see below).

- Beak: pointed end that sticks out along the hinge line

- Brachial (dorsal) valve: the smaller half of the shell, which supports the lophophore

- Brachidium: calcareous supports for the lophophore feeding organ

- Commissure: the line where both valves meet when closed

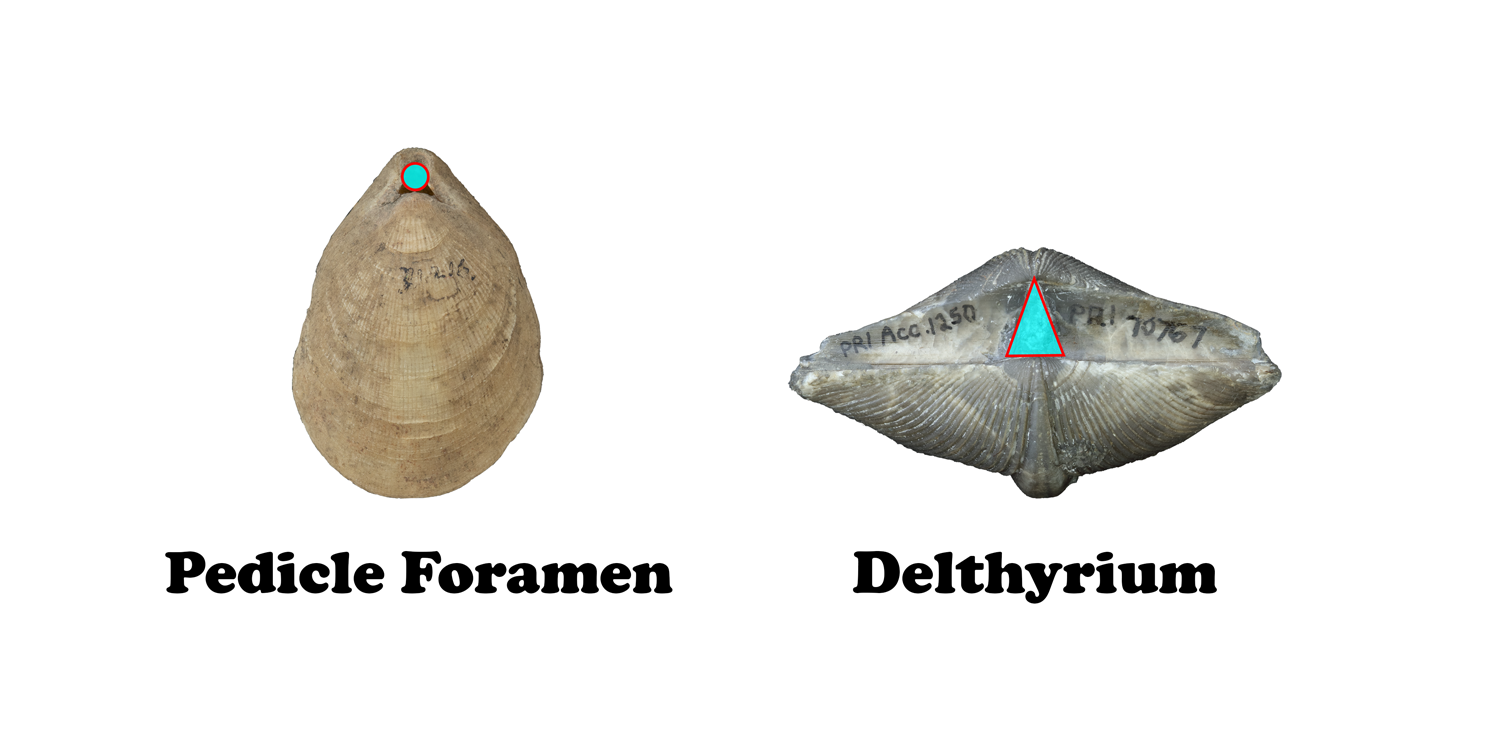

- Delthyrium: triangle or notch-shaped opening in the ventral valve through which the muscular pedicle emerges

- Fold: the raised up, ‘tented’ area down the midline of the brachial valve (opposite the sulcus)

- Growth line: concentric lines down the shell from the beak to the commissure which marks growth over time

- Hinge teeth: bumps along the inside of the hinge line of the pedicle valve; the brachial valve has corresponding dental socket depressions

- Lophophore: cilia lined organ used for feeding and respiration

- Pedicle: fleshy stalk-like organ used for attachment

- Pedicle foramen: rounded opening in the ventral valve through which the muscular pedicle emerges

- Pedicle (ventral) valve: the larger half of the shell which attaches to the pedicle

- Plication: an elaborately wavy surface on the shell surface, which looks like zigzags along the commissure

- Sulcus: depression, ‘valley’, down the midline of the ventral valve (opposite the fold)

Reconstruction of half of an articulated terebratulide brachiopod sectioned along the plane of symmetry to expose internal anatomy. Image from Figure 1 of Carlson (2016). Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Brachiopod morphology. Image by Jaleigh Q. Pier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Modern brachiopod specimen from the teaching collection of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York. Longest dimension of specimen is approximately 4 cm.

Brachial valve of a modern brachiopod specimen. Specimen is from the teaching collection of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York. Longest dimension of specimen is approximately 4 cm.

Pedical valve of a modern brachiopod specimen. Specimen is from the teaching collection of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York. Longest dimension of specimen is approximately 4 cm.

Interactive 3D model showing fold and sulcus of the fossil brachiopod Mediospirifer audaculus from the Middle Devonian Moscow Formation of Livingston County, New York (PRI 70767). Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York. Longest dimension of specimen is approximately 5 cm.

Lophophore

The organ that brachiopods use for both feeding and respiration is called the lophophore. The lophophore is lined with tiny hair-like cilia which generate a water current through the shell, transporting both oxygen and food particles. Some species have a calcified support structure for the lophophore called a brachidium. Brachiopods aren’t the only group to possess a lophophore; bryozoans and marine horseshoe worms (phoronids) are also lophophorates.

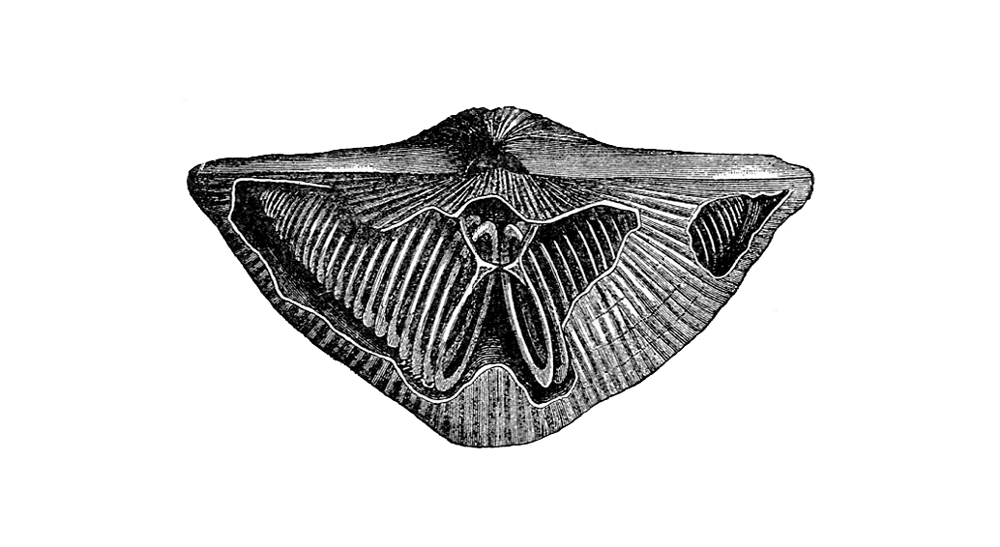

Spiralia brachidium of Spirifer striatus from the Lower Carboniferous of Ireland (Zittel 1913, Fig. 622.). (Public Domain)

Diversity of brachiopod internal lophophore supports known as brachidia (Zittel 1913, Fig. 531). (Public Domain)

Interactive 3D model of a preserved brachidium from the fossil brachiopod Athyris subtilita (PRI 76883). Specimen from the Paleontological Research Collection, Ithaca, New York. Longest dimension is approximately 2 cm.

Pedicle

Unique to brachiopods is the fleshy, stalk-like pedicle, which some groups use to attach to hard substrates. Although rarely preserved itself, brachiopod shells will often have a pedicle opening preserved along the hinge-line called the pedicle foramen. If the pedicle opening is more triangular in shape instead of round, it is called a delthyrium. See an example of what an attached pedicle looks like with the lingulid 3D model below!

Pedicle opening shapes. Image by Jaleigh Q. Pier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Living Brachiopods

Although you probably haven't seen one up close before, brachiopods are in fact still alive today. Most species occupy deep and cold marine habitats, perhaps because they have not been able to ecologically compete with other benthic invertebrates (such as bivalves) in shallower, warmer habitats. Living brachiopods have been found in depths up to 4000m (that's almost two and a half miles!), but are more commonly encountered between depths of 0–500 m range and often in gregarious abundances.

Brachiopod closes valves at 3:51 and video is centered at 4:57. Video courtesy of Systematisk Zoologi.

Only 5% of all brachiopod species to ever exist still survive today, while 95% have gone extinct. Members from the orders Lingulata, Rhynconellida, and Terebratulida are among those that exist today. Below are a few examples of some of these living brachiopods, which will be explained in more detail on the next page.

Recent brachiopod specimen of Terebratulina septentrionalis from the coast of Maine (PRI 76877). Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York. Longest dimension of specimen is approximately 2.5 cm.

Recent specimen of the brachiopod Terebratalia transversa from Salt Spring Island, B.C. Canada (PRI 76884). Specimen from the Paleontological Research Collection, Ithaca, New York. Longest dimension is approximately 12.5 cm.

Recent specimen of the brachiopod Lingula anatina from the Phillipines (PRI 76882). Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York. Longest dimension of specimen is approximately 6 cm.

References and further reading

Boardman, R.S., Cheetham, A.H., and Rowell, A.J. 1987. Fossil Invertebrates. Blackwell Scientific Publications. 713 pp.

Carlson, S.J. 2016. The Evolution of Brachiopoda. Annual Reviews of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 44:409-438.

Rudwick, M.J.S. 1970. Living and Fossil Brachiopods. London: Hutchinson Univ. Libr.

Sandy, M.R. 2001. Life Beyond the Permian--Mesozoic-Cenozoic Brachiopod Paleobiogeography, paleoecology, and evolution, in Carlson, S.J. and Sandy, M.R. ed., Brachiopods Ancient and Modern. The Paleontological Society Papers, Volume 7:223-247.

A. Selden ed., Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part H, Brachiopoda Revised, Volume 6. The University of Kansas and Geological Society of America. 3226 pp.

Tree of Life Web Project. 2002. Brachiopoda. Lamp shells. Version 01 January 2002 (temporary). http://tolweb.org/Brachiopoda/2494/2002.01.01 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Zittel, K.A. 1913. Brachiopoda, in Eastman, C.R. ed., Text-Book of Paleontology. Macmillan and Co. Limited, London. 839 pp.

Usage

Unless otherwise indicated, the written and visual content on this page is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This page was written by Jaleigh Q. Pier. See captions of individual images for attributions. See original source material for licenses associated with video and/or 3D model content.