Reptiles arose from amphibians in the late Carboniferous Period, evolving adaptations for life in dry environments such as scaly skin and a shelled egg that can be laid on land. Most reptile groups that dominate today originated in the Mesozoic era. Living reptiles include snakes, lizards, crocodiles, and turtles; most of these groups contain members that look very similar to their Mesozoic forebears. Reptiles also include dinosaurs and their descendants, the birds. Birds are not typically considered living fossils, however, due to their more recent evolutionary origin.

Tuataras are small (2-3 foot) lizard-like reptiles that live only in New Zealand. As the only remaining species of a once-diverse reptile group, the tuatara survived the ages in New Zealand’s isolated and predator-free island environment.

"What on Earth Is A Tuatara? | Modern Dinosaurs" by Discovery UK (YouTube).

Modern taxodermy specimen of a tuatara (Sphenodon) from New Zealand. Length of specimen is approximately 50.5 cm.

Although tuataras were originally described as lizards in the 1830s, they were recognized as part of a separate group, the rynchocephalians, in 1867. Rynchocephalians were widespread during the Triassic, but their fossils have not been found past the Mesozoic.

Tuataras differ from lizards in several ways. They have two rows of upper teeth, and the lower teeth are fused to the jaw. Additionally, there are two circular side openings in the skull, instead of just one as in lizards. This allows for larger jaw muscles.

Annotated model of a tuatara skull from the collections of the Florida Museum of Natural History (UF 11978). Note two rows of upper teeth. Source: UF Herpetology on Sketchfab.

↑↓ Compare

Annotated model of a green iguana skull from the collections of Ohio University (OUVC 10677). Note the single rows of teeth. Source: WitmerLab at Ohio University.

Tuataras are slow-moving and nocturnal. They reach reproductive age between 15 and 20 years, and females lay eggs every 4 years. Their lifespan can reach well over 100 years, and reproduction has occurred in captivity at the age of 111. The name “tuatara” is from the Maori language, and means “peaks on the back.”

Conservation Connection

Tuataras’ slow growth and metabolism, makes them vulnerable to predators. Millions of tuataras were once widespread across both islands of New Zealand. When the first humans arrived from Polynesia around the year 1200, they brought rats and dogs with them. These predators, along with cats and ferrets brought later by Europeans, wiped out most of the tuatara population.

Today, tuataras live on 35 islands off the New Zealand coast, and their population includes around 100,000 individuals. There is one living species, with another possibly driven extinct by humans. Tuataras are regarded as a national treasure of New Zealand and they have been legally protected since 1895. The New Zealand Department of Conservation launched a tuatara recovery program in 1988, which maintains several successful captive breeding programs.

Crocodilians, a reptile group including alligators, caimans, crocodiles, and gharials, are frequently seen as ancient holdovers from the days of the dinosaurs. Their number includes the largest living reptile, the saltwater crocodile, which can reach lengths of up to 18 feet. Crocodilians are archosaurs, a group of reptiles that also includes pterosaurs (flying reptiles), dinosaurs, and their descendants, the birds.

A saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus). Photograph taken by Jonathan R. Hendricks at a crocodile farm near Cairns, Australia.

There are 23 species of living crocodilians found throughout the world’s tropics and warm temperate regions. Modern crocodilian diversity is low compared to its fossil record, which extends back to the Late Cretaceous period (about 80 million years ago). Fossil crocodilians outnumber their living relatives five to one, and are found on every continent, including Antarctica.

Modern crocodilians look extremely similar to their prehistoric counterparts: all are semiaquatic ambush predators with flattened snouts and teeth set in sockets. Because of this, they are often thought to be unchanged since the Mesozoic. Even though they may look similar from a distance, however, crocodilians’ evolutionary history has been extremely dynamic. Fossil crocodilians include a diversity of body forms and sizes. Their evolutionary history includes multiple trans-oceanic crossings and episodes of diversification. Although rates of evolutionary change have been slow in some branches of their family tree, they have been rapid in others. For example, all of the species of Crocodylus (the “true” crocodiles), a group long thought to be more ancient, probably last shared a common ancestor less than 15 million years ago.

Conservation Connection

Most modern crocodilian populations have suffered from overhunting and habitat loss during the twentieth century, but although some remain “critically endangered”, others are real success stories in conservation biology. For example, the American alligator was at the brink of extinction in the mid-20th century, but has made a dramatic comeback thanks to regulation and captive breeding. Six crocodilian species, including the Chinese alligator and Indian and Malayan gharials, are currently listed as “endangered”, while another three, including the American crocodile, are listed as “vulnerable.”

Although we don’t often think of snakes as living fossils, they have been around since the Jurassic Period. Descendants of lizards, snakes lost their limbs during the course of evolution. Many of the most primitive modern snakes, pythons and boas, have vestigial hind limbs, and some also have remnants of a pelvis.

The oldest known snake fossils, from over 150 million years ago, are already recognizable as snakes from the shapes of their skulls, which have unique backward-pointing teeth to help capture prey. Snake fossils from the Late Cretaceous (between 98 and 80 million years ago) still have two hind limbs, though they had lost their front legs by that time. By the Eocene, 50 million years ago, snake fossils are extremely similar to modern snakes.

The four-legged snake Tetrapodophis amplectus from the Early Cretaceous of Brazil. Image by "Ghedoghedo" (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license).

↑↓ Compare

CT scanned skeleton of the modern white-banded wolf snake, Lycodon subcinctus. Model by the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (Sketchfab).

Around 58 million years ago, not long after the extinction of the dinosaurs, lived a snake that may have reached a ton in weight and 40 feet in length. Fossil bones of this gigantic snake, Titanoboa, were found in Colombia in the early 2000s. Titanoboa was closely related to modern anacondas, members of the boa family. This skull reconstruction was built by making a 3D scan of an anaconda skull, modifying it based on the fragmentary fossils of Titanoboa, and then enlarging and printing it on a 3D printer.

Reconstruction of the skull of the Paleocene snake Titanoboa. 3D model made from cast. Original specimen found in Columbia. Length of specimen is approximately 40 cm.

Amazing Adaptation: Sensitive Skull

The boa constrictor (Boa constrictor) has eyes with vertical pupils that help the snake see its prey in dim light, but it senses nearby animals in other ways too. Not by hearing them—the boa constrictor doesn't have external ears like ours—but by feeling vibrations in the ground! The snake's jawbones can sense movement in the ground or in the air, leading it to its next meal.

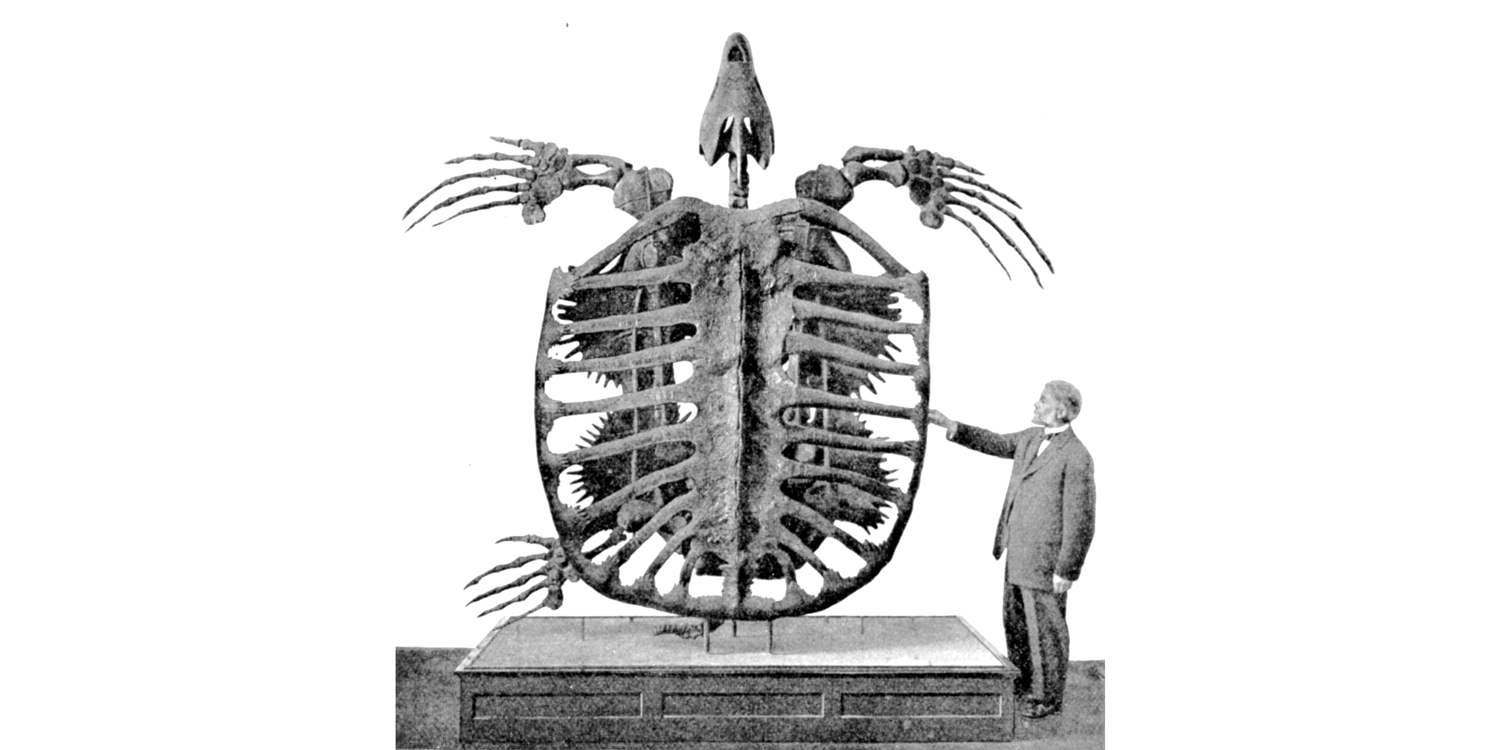

Turtles are very distinctive reptiles, characterized by their bony shell, or carapace. They are frequently thought of as “ancient” and therefore as classic examples of living fossils. The oldest known fossil of a turtle ancestor, a discovery just announced in 2018, comes from Chinese rocks that date to the Triassic period (around 228 million years old). Modern-looking turtles were numerous by the Cretaceous period, 150 million years ago.

A juvenile snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) in Athens, Ohio. Photograph by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

The turtle body plan is one of the strangest–and in a way the most evolved–of any backboned animal. The most conspicuous characteristic of turtles, the shell, is made of expanded and fused ribs. And, unlike all other vertebrates, turtles’ shoulder blades and hip bones are inside their rib cage. Exactly how this dramatic evolutionary transformation took place is still not fully understood.

Interactive 3D model of a modern mata mata turtle (Chelus fimbriata) skeleton. Model created by the Idaho Museum of Natural History (Sketchfab).

Scientists are also uncertain about which reptiles are most closely related to turtles. Until recently, it was widely thought that turtles have a more primitive body form, and branched off from the other reptiles very early. However, recent evidence from both genetics and anatomy suggests that the closest relatives of turtles are snakes, or even crocodilians and other close relatives of dinosaurs. This debate is currently an active topic in vertebrate paleontology.

Fossil skeleton of the giant Cretaceous sea turtle Archelon. Image is from the book "Animals of the Past" by Frederic A. Lucas (1902) (Wikimedia Commons; public domain).

Modern skull of the green sea turtle Chelonia mydas from the Atlantic Ocean. Specimen is from the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates. Length of skull is approximately 19 cm.

Sea turtles have many features that set them apart from land turtles. They have flippers, a streamlined body that reduces drag, and cannot retract their heads into the shell. Sea turtles include the largest turtle to have ever lived–Archelon (shown above), a 4900-pound sea turtle from the Late Cretaceous–and the largest turtles alive today, the leatherbacks, which reach up to 1500 pounds. The shell of a leatherback is reduced to a thin mosaic of bony scutes, which reduces their weight. They are endothermic, generating their own body heat through muscle activity, which is useful in cold ocean water. They eat almost exclusively jellyfish, they can dive to more than 2000 feet, and individuals probably swim farther than any other vertebrate species in the sea. Leatherback turtles are also ancient – the oldest ones are known from the Late Cretaceous period, around 70 million years ago. The oldest known sea turtle, discovered in 2015, is around 120 million years old.

Amazing Adaptation: Long Inactivity

The Russian tortoise (Agrionemys horsfieldii) is native to the rocky hillsides and sandy grasslands of Russia, Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. Because of the extreme temperatures in this region, the tortoise stays in its burrow for most of the year. It emerges from its tunnel in early spring to mate and lay its eggs, then heads back into its burrow in June or July.

Contents: Introduction | Microbialites | Plants | Echinoderms | Fishes | Reptiles | Opossum | Brachiopods | Mollusks | Horseshoe Crabs | Insects & Arachnids