Mollusca

– 2. Cephalopoda

–– 2.1 Cephalopoda stem groups

–– 2.2 "Nautiloidea" ←

–– 2.3 Ammonoidea

–– 2.4 Coleoidea

–– 2.5 Quiz

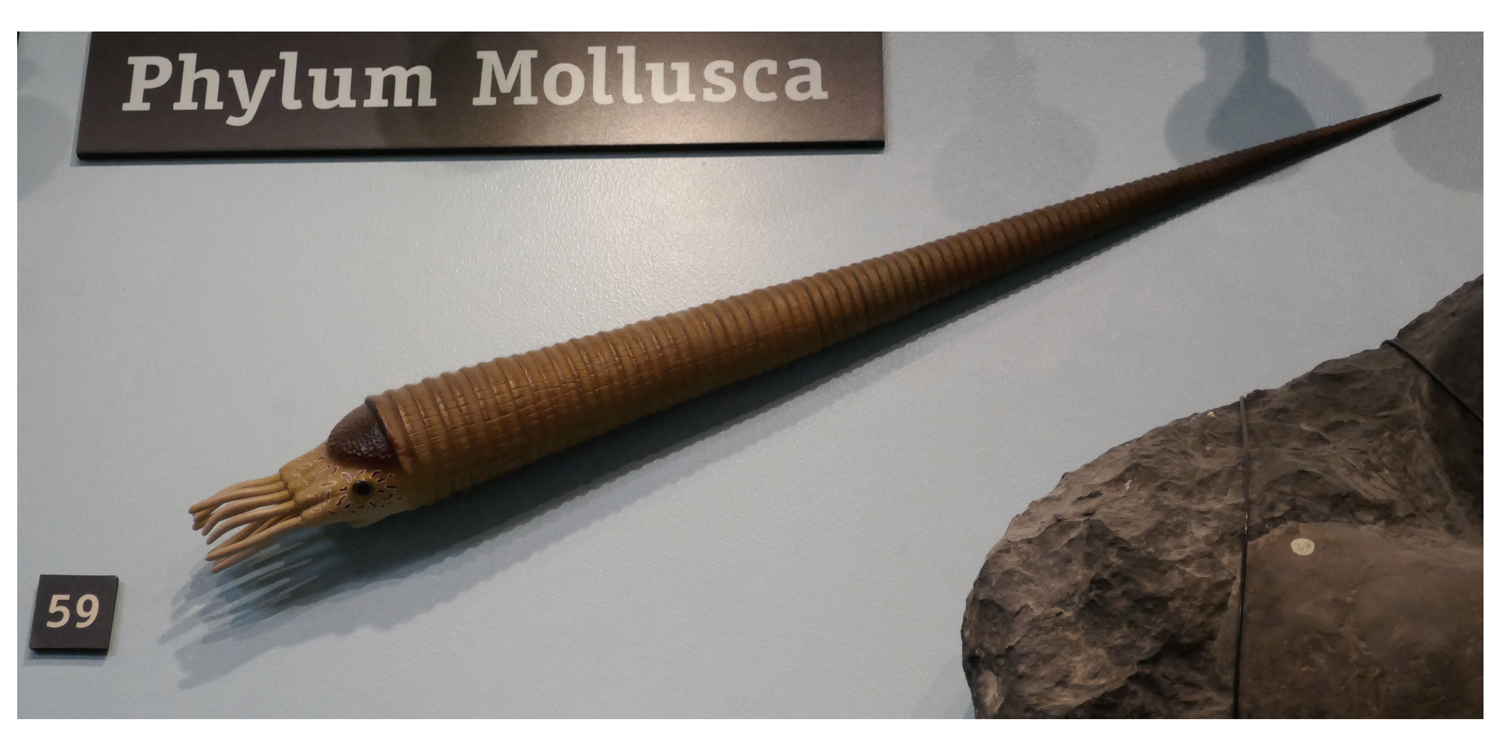

Above: Diorama of Ordovician that once lived near Cincinnati, Ohio; on display at the American Museum of Natural History, New York. Photograph by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

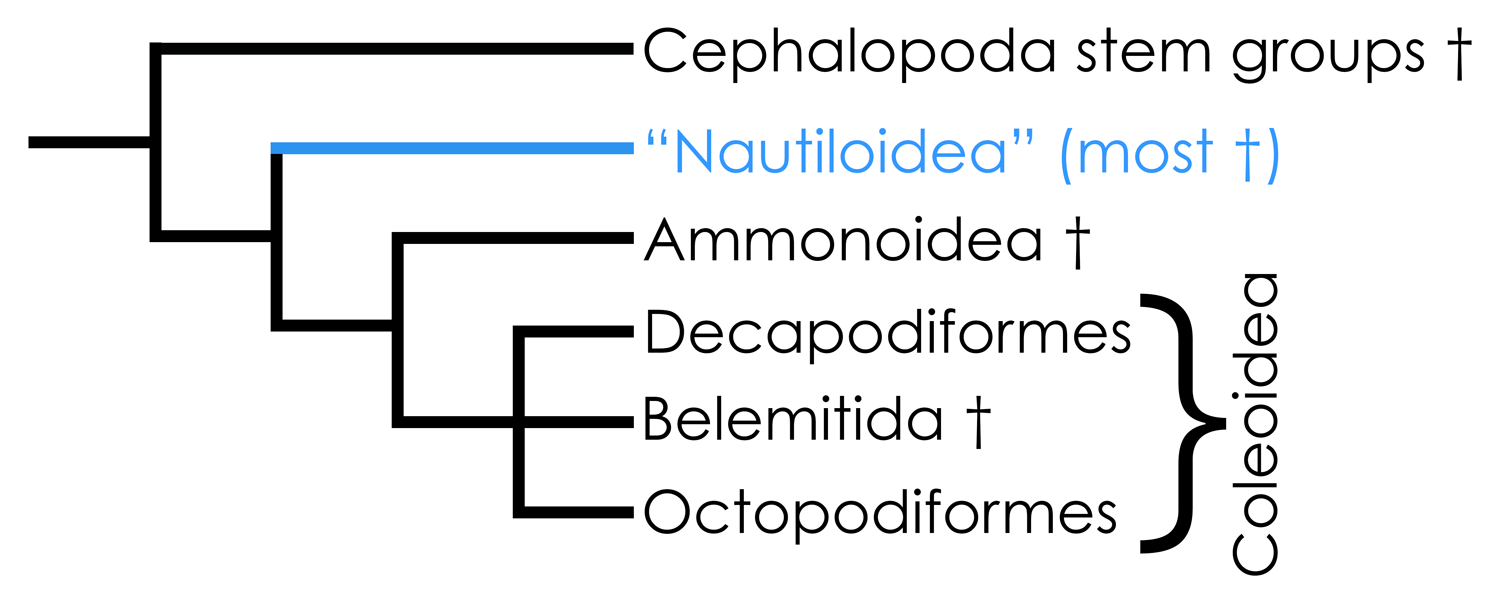

Highly simplified overview of cephalopod phylogeny based in part on the hypothesis of relationships presented by Kröger et al. (2011). Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

The group "Nautiloidea" is represented today by two similar genera, Allonautilus (1 or 2 species) and the more familiar Nautilus (also known as the "chambered nautilus"; 8 species), which you were introduced to at the start of this chapter. The external shells of these two genera differentiate them from all other extant cephalopods (Coleoidea), which either have an internal shell, a greatly reduced shell, or no shell at all.

Allonautilus and Nautilus are not closely related to other extant cephalopods (squids, cuttlefish, and octopuses) and in many ways are very different, as explained in the video below by cephalopod expert Dr. Neil Landman (American Museum of Natural History). In particular, they are scavengers, hatch from large eggs, and have long lives.

Numerous Paleozoic cephalopod species have been assigned to the "Nautiloidea" based on similarities of shell structure that they share with the chambered nautilus, especially their gently-curving internal sutures. While extant nautiloids have tightly-coiled shells, extinct species showed a much greater diversity of forms, including groups characterized by having long, straight shells (orthoconic longicones).

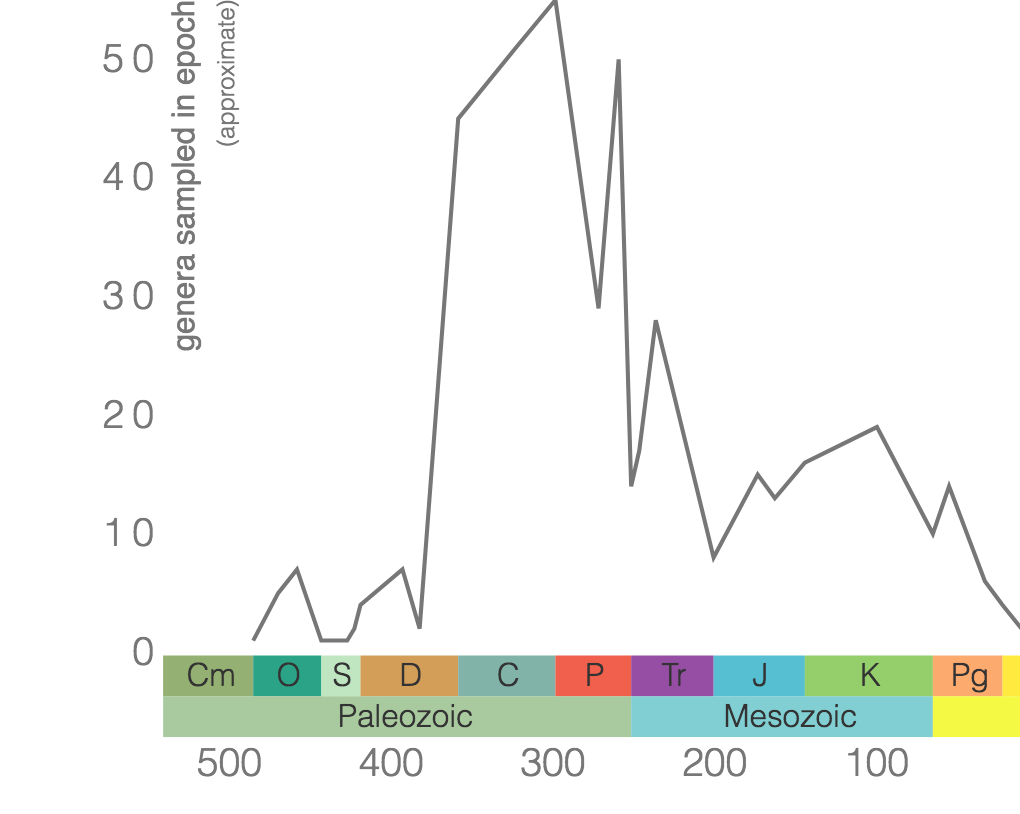

Nautiloids originated in the Ordovician period and reached their greatest genus-level diversity late in the Paleozoic. Their diversity declined greatly during the end-Permian and end-Triassic mass extinction events and never again recovered to prior levels of diversity following the Triassic. Even so, they were very important predators in Paleozoic marine ecosystems, especially before the rise and radiation of the ammonoids.

Phanerozoic genus-level diversity of "Nautiloidea" (graph generated using the Paleobiology Database Navigator).

It is clear that overall nautiloid shell form shows many instances of evolutionary convergence: similar shell forms have evolved multiple times among different subgroupings of nautiloids. This has complicated attempts to determine their phylogenetic relationships, as well as develop a stable classification (though numerous attempts have been made). Indeed, the group "Nautiloidea" (as used here) is almost certainly paraphyletic, as the ammonoids and coleoids are likely descendants of one particular group of cephalopods that has been assigned to the Nautiloidea (see below). Examples of several (though not all) of the major groups of "Nautiloidea" are provided below.

Nautilida

The modern chambered nautilus belongs to the Nautilida group, which characteristically have "closely coiled, widely umbilicate to convolute and involute" (Teichert and Moore, 1964a, p. K98) shells. They originated in the Devonian and persist to the present day. Some fossil examples are below.

Goldringia undulata from the Devonian Onondaga Limestone of Sangerfield, New York. Note the gyroconic shell of this species. Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York (PRI 70576). Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Tetranodoceras transversum from the Marcellus Shale (Cherry Valley Limestone Member) of Cayuga County, New York. Note the gyroconic coiling of this species. Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York (PRI 5365). Model by Emily Hauf; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license (CC BY-SA 4.0).

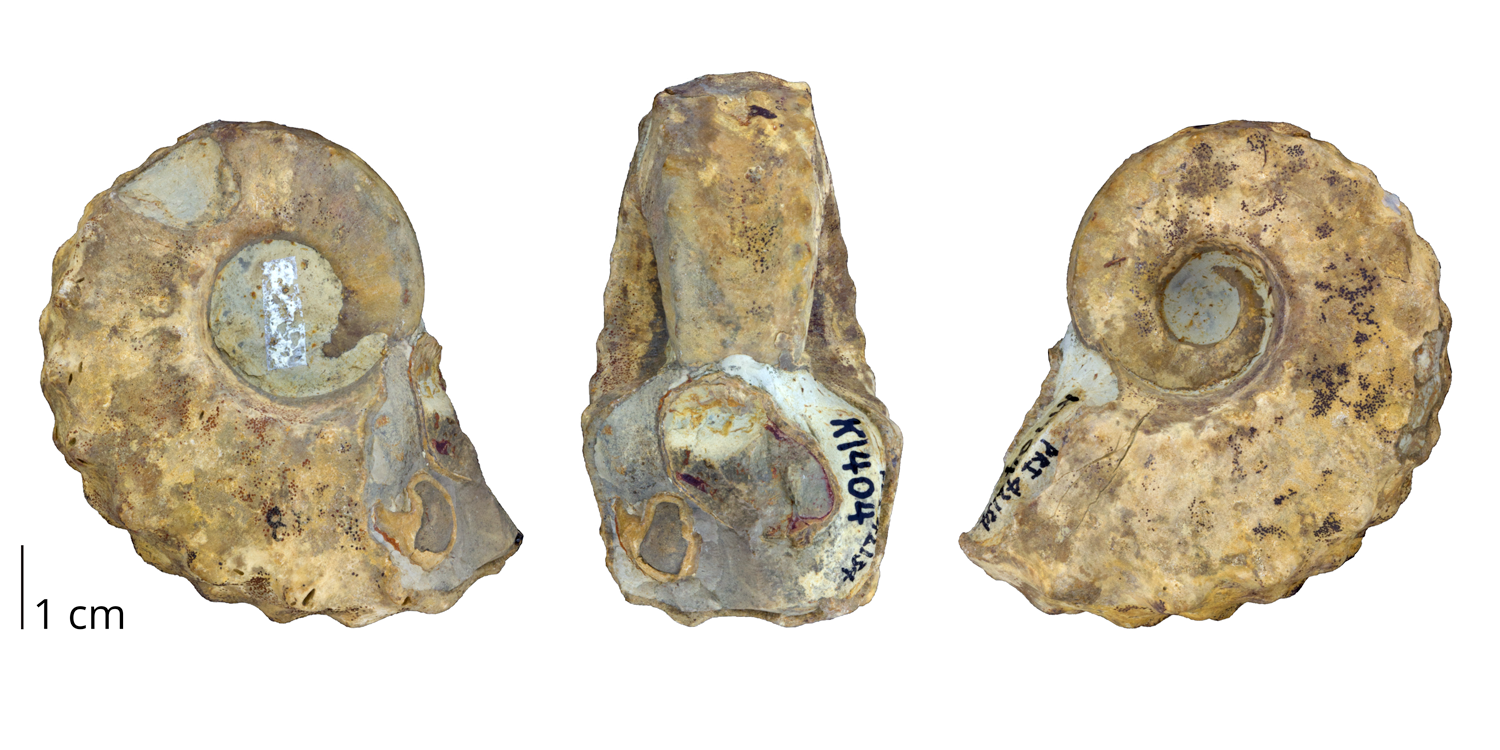

Tainoceras monilifer from the Pennsylvanian Graford Formation of Palo Pinto County, Texas. Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York (PRI 42134). Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

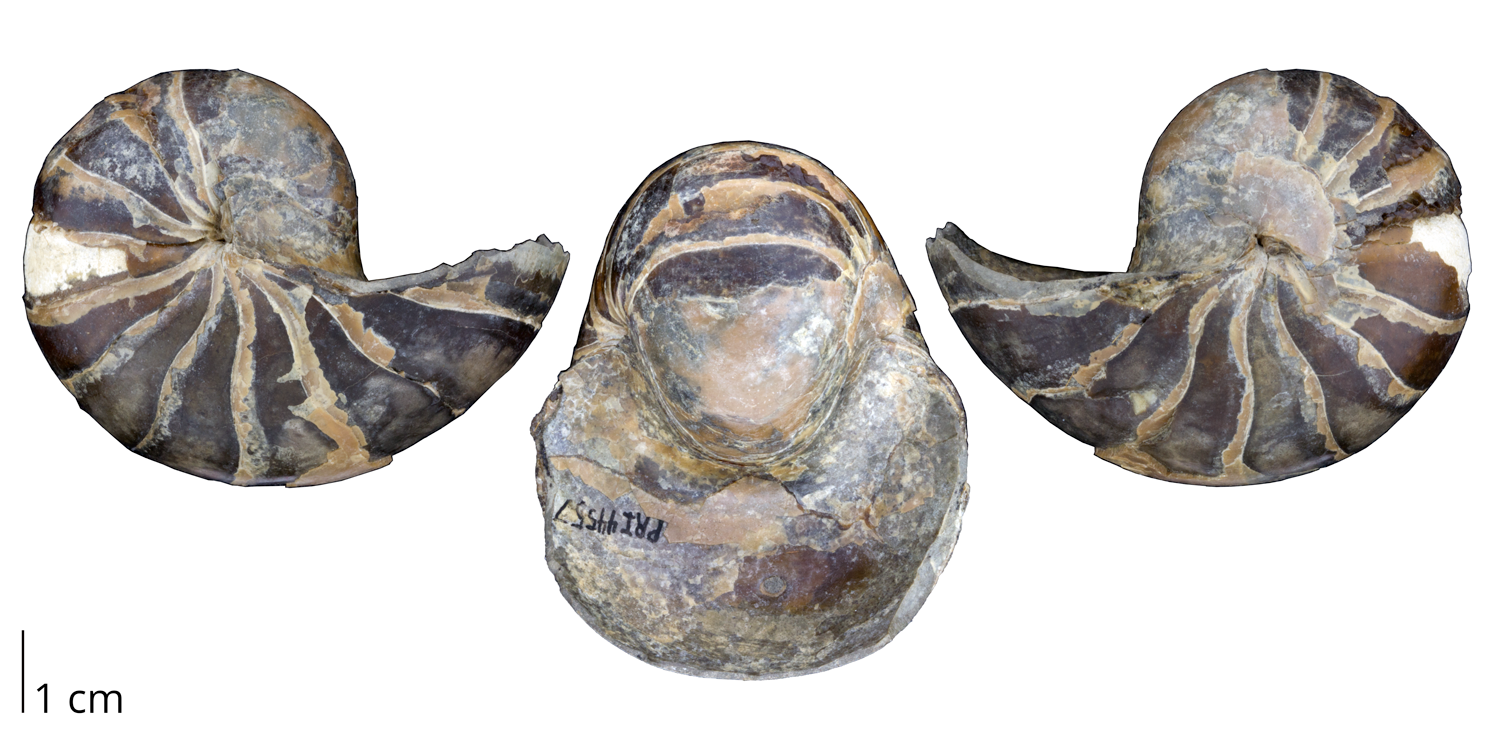

Eutrephoceras dekayi from the Cretaceous Pierre Shale of South Dakota. Note the involute shell of this species. Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York (PRI 44557). An interactive 3D model of this specimen is immediately below. Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Interactive 3D model of Eutrephoceras dekayi from the Cretaceous Pierre Shale of the Black Hills of South Dakota (PRI 44557). Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York. Maximum diameter of specimen is approximately 6 cm. See photographs of this specimen above. Model by Emily Hauf; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Aturia angustata from the Oligocene of Pacific County, Washington. Note the jagged-shape of the suture of this species. Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York (PRI 70323). Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

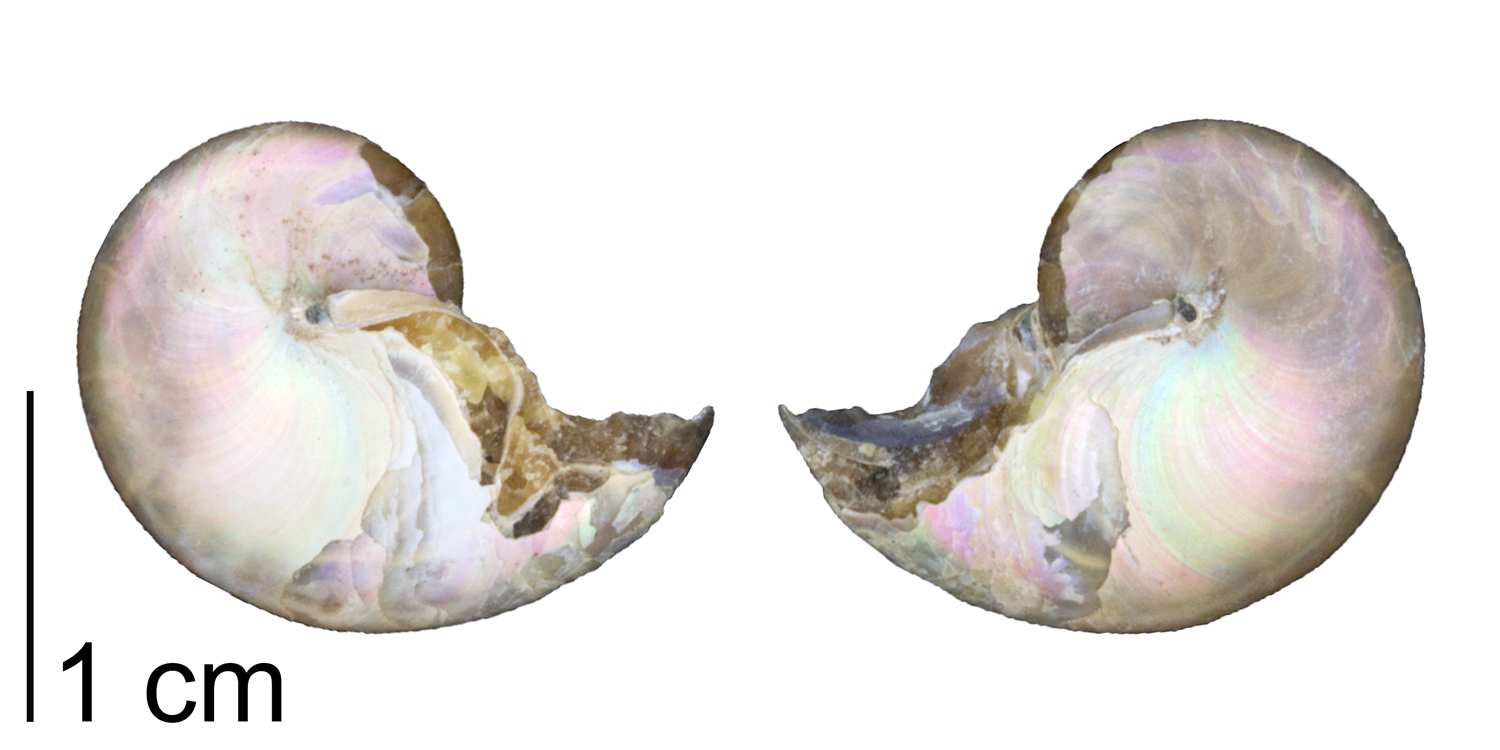

Aturia angustata fro the Oligocene of Washington. Note the iridescent original external shell of this specimen. Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York (PRI 70367). Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Aturia curvilineata from the Miocene Subibaja Formation of Ecuador. Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York (PRI 70322). Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Tarphycerida

Tarphycerids typically had coiled shells and are known from the Ordovician and Silurian periods (Teichert and Moore, 1964a, p. K98).

Eurystomites kelloggi from the Ordovician of New Mexico. Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York (PRI 73791). Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Graftonoceras graftonensis from the Silurian of Illinois. Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York (PRI 70321). Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Actinocerida

According to Teichert and Moore (1964b), Actinocerida--which ranged from the Ordovician to the Pennsylvanian--are characterized by "[m]edium-sized to very large, generally straight" shells with segments that are "typically wider than long" and "large siphuncles generally with broad contact of segments with [the] ventral wall of [the] shell" (p. K129).

Fragment of Actinoceras beloitense from the Middle Ordovician Platteville Formation of Illinois. Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York (PRI 70326). An interactive 3D model of this specimen is immediately below. Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Interactive 3D model of Actinoceras beloitense from the Ordovician Platteville Limestone of Ogle County, Illinois (PRI 70326). Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York. Length of specimen is approximately 9 cm. Photographs of this specimen are above. Model by Emily Hauf; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Endocerida

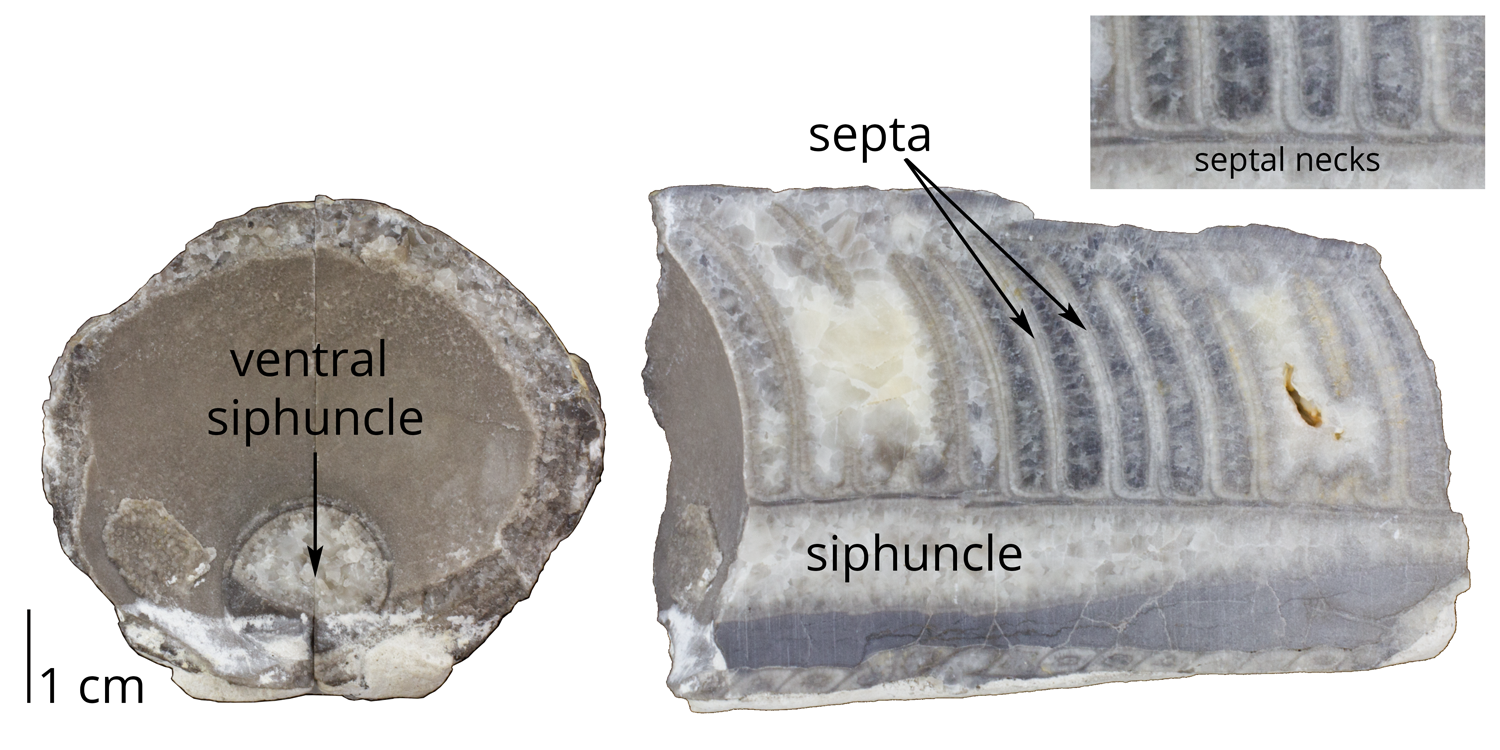

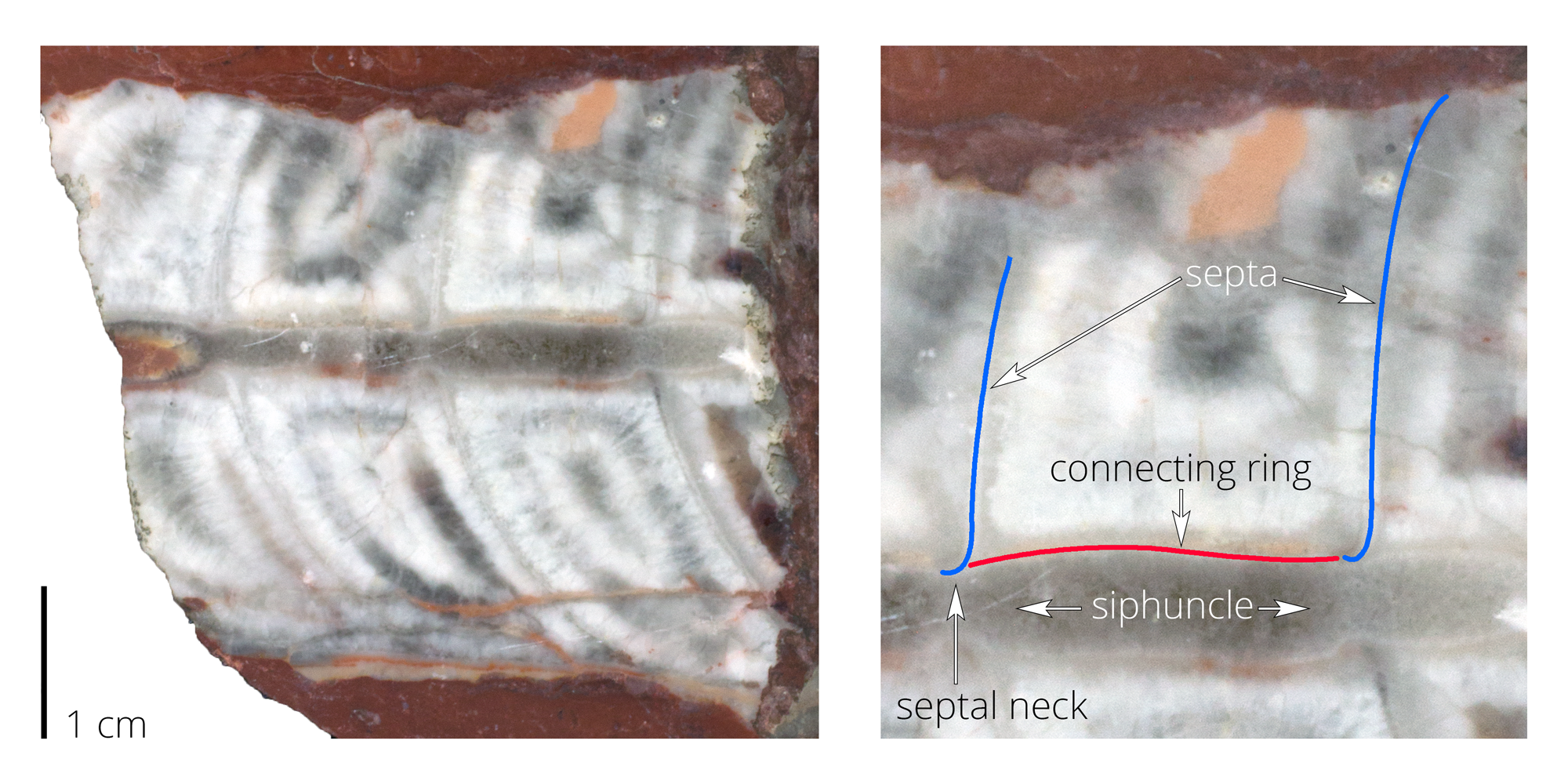

Members of the Endocerida are notable for the very large, long, orthoconic shells of some species. For example, some Cameroceras specimens are estimated to have reached lengths of 6 m. The siphuncles of endocerids differentiate them from other subgroups of Nautiloidea. In particular, their siphuncles "occupied a major part of the [shell] ... not just a siphuncular cord" (Teichert and Moore, 1964b, p. K128). This can be observed in the specimens shown below. Endocerids are best known from the Ordovician, but may have survived into the Silurian.

Vaginoceras oppletum from the Ordovician Chazy Formation of Clinton County, New York. Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York (PRI 70578). Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Endoceras multilobatum from the Ordovician Black River Limestone of Jefferson County, New York. Specimen from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York (PRI 70584). Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

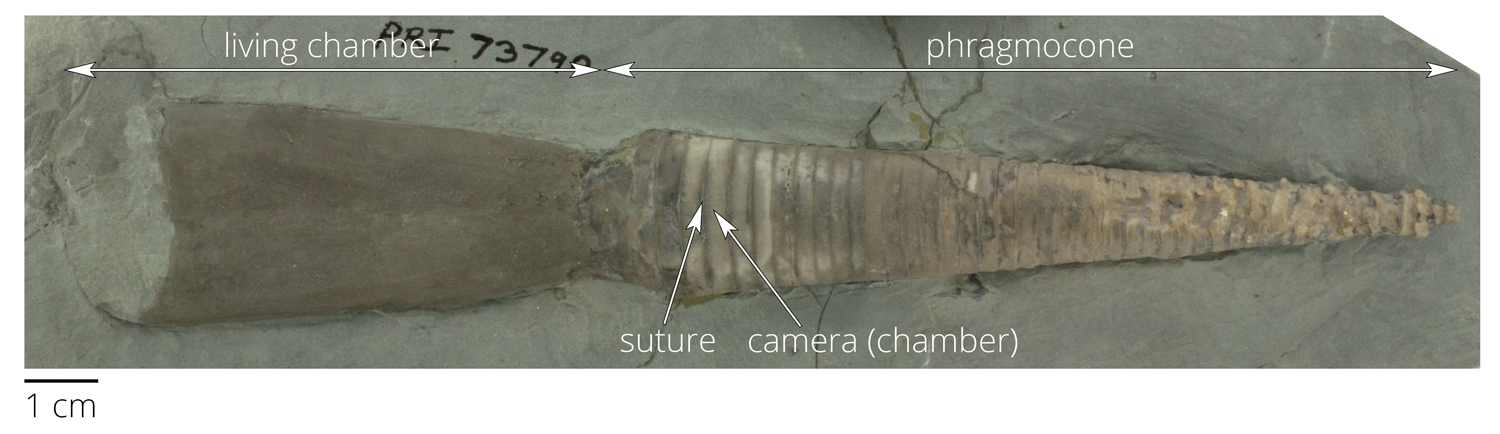

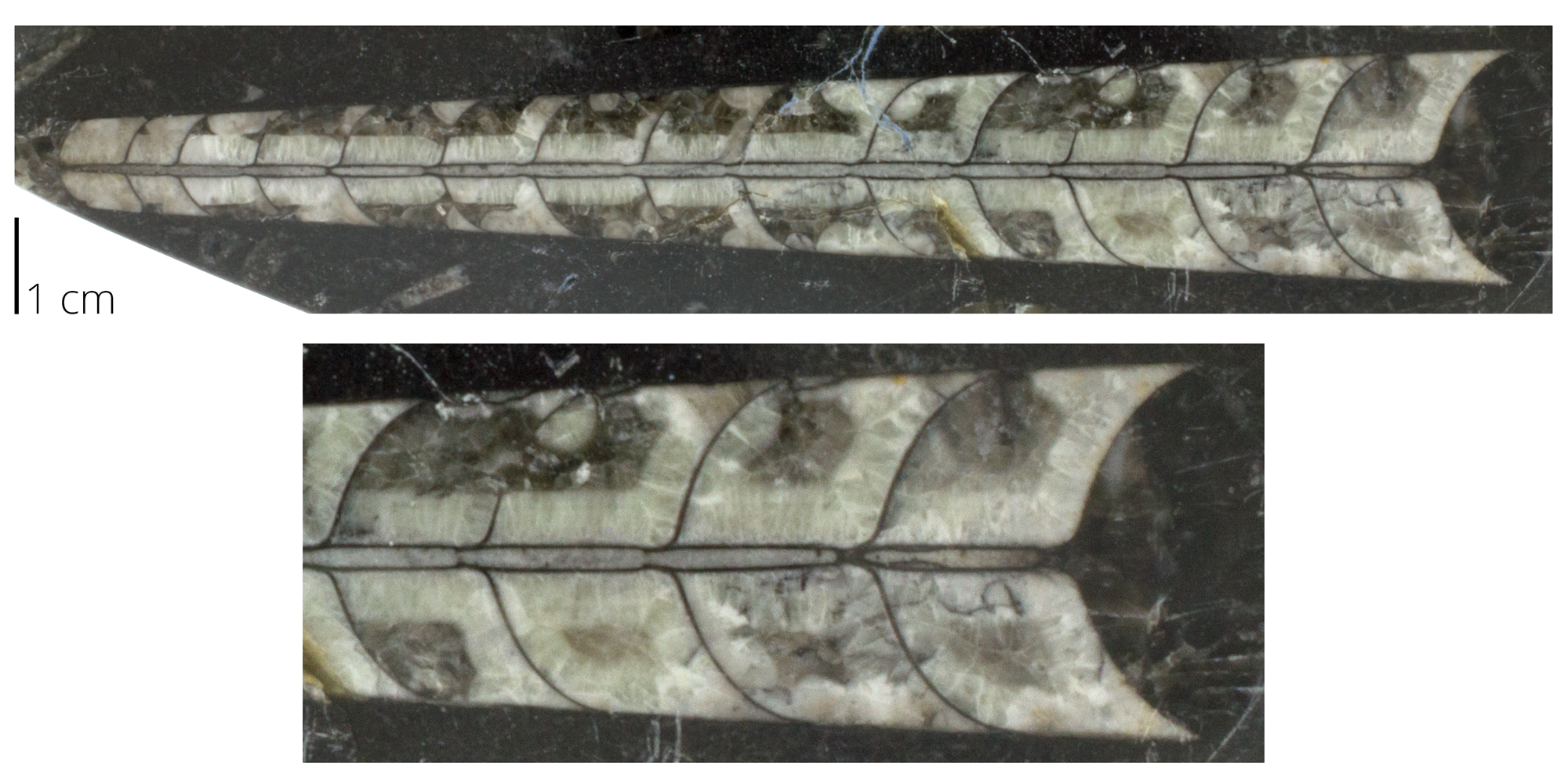

Orthocerida

Orthocerida is a major grouping of extinct cephalopods, which ranged from the Early Ordovician to the Late Triassic, though are best known from the early Paleozoic. Contrasting somewhat with other ancient cephalopod groups, the shells of orthocerids tended to be straight and long (orthoconic longicones), though some species have shells that were slightly curved (Sweet, 1964). Orthocerids represent a notable offshoot of Nautiloidea: they apparently gave rise to the bactritids, from which the ammonoids and coleoids likely evolved (see below).

Treptoceras cincinnatiensis from the Ordovician of Warren County, Ohio (PRI 73790). Learn more about this genus on the Ordovician Atlas of Ancient Life. Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Orthoceras sp. (no other information about this specimen is available, though it is likely from the Ordovician of Morocco) (PRI 70587). Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Michelinoceras sp. from Sweden (PRI 70582). Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Treptoceras cf. duseri from the Ordovician Richmondian Stage of Cincinnati, Ohio. Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution (PRI 45492). Maximum length of specimen is approximately 17 cm. Model by Emily Hauf; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Spyroceras sp. from the Devonian Moscow Formation of Cayuga County, New York. Specimen from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York (PRI 70327). Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Model reconstruction of Spyroceras on display at the Museum of the Earth, Ithaca, New York. Compare with specimen immediately above. Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Spyroceras sp. from the Devonian of Onondaga County, New York. Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York (PRI 70598). Length of specimen is approximately 4.5 cm. Model by Emily Hauf; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Bactritida

The Bactritida is a somewhat obscure group of extinct cephalopods that are nevertheless notable because they apparently gave rise to two major groups: the ammonoids and the coleoids (Klug et al., 2015). Bactritids evolved from orthocerids (see above) and share several synapomorphies with them, including "the small subspherical to ovoid initial chamber, the straight to slightly bent conical shell and the narrow siphuncle" (Klug et al., 2015, p. 12). This group originated in the Ordovician and went extinct in the Permian (Erben, 1964).

Bactrites smithianus from the Mississippian Chesteran Caney Shale (Delaware Creek member) of Coal County, Oklahoma. Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York (PRI 70366). Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

References and further reading:

Erben, H. K. 1964. Bactritoidea. Pp. K491-K505, in: Teichert, C., B. Kummel, W. C. Sweet, H. B. Stenzel, W. M. Furnish, B. F. Glenister, H. K. Erben, R. C. Moore, and D. E. Nodine Zeller (eds.), Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part K, Mollusca 3. The Geological Society of America and The University of Kansas Press, Lawrence, 519 pp.

Klug, C., B. Kröger, J. Vinther, D. Fuchs, and K. De Baets. 2015. Ancestry, origin and early evolution of ammonoids. Pp. 3-24, in: Ammonoid Paleobiology: From Macroevolution to Paleogeography. Topics in Geobiology 44, Springer Science+Business Media.

Kröger, B., J. Vinther, and D. Fuchs. 2011. Cephalopod origin and evolution: a congruent picture emerging from fossils, development and molecules. Bioessays 33: 602-613. Link.

Sweet, W. C. 1964. Nautiloidea-Orthocerida. Pp. K216-K261, in: Teichert, C., B. Kummel, W. C. Sweet, H. B. Stenzel, W. M. Furnish, B. F. Glenister, H. K. Erben, R. C. Moore, and D. E. Nodine Zeller (eds.), Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part K, Mollusca 3. The Geological Society of America and The University of Kansas Press, Lawrence, 519 pp.

Teichert, C. and R. C. Moore. 1964a. Classification and stratigraphic distribution. Pp. K94-K106, in: Teichert, C., B. Kummel, W. C. Sweet, H. B. Stenzel, W. M. Furnish, B. F. Glenister, H. K. Erben, R. C. Moore, and D. E. Nodine Zeller (eds.), Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part K, Mollusca 3. The Geological Society of America and The University of Kansas Press, Lawrence, 519 pp.

Teichert, C. and R. C. Moore. 1964b. Introductory discussion. Pp. K127-K129, in: Teichert, C., B. Kummel, W. C. Sweet, H. B. Stenzel, W. M. Furnish, B. F. Glenister, H. K. Erben, R. C. Moore, and D. E. Nodine Zeller (eds.), Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part K, Mollusca 3. The Geological Society of America and The University of Kansas Press, Lawrence, 519 pp.

Usage

Unless otherwise indicated, the written and visual content on this page is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This page was written by Jonathan R. Hendricks. See captions of individual images for attributions. See original source material for licenses associated with video and/or 3D model content.