Chapter contents:

Porifera

–– 1. Archaeocyatha

–– 2. Stromatoporoidea

–– 3. Demospongiae ←

–– 4. Hexactinellida

–– 5. Calcarea

–– 6. Homoscleromorpha

3D models of Demospongiae can be found here!

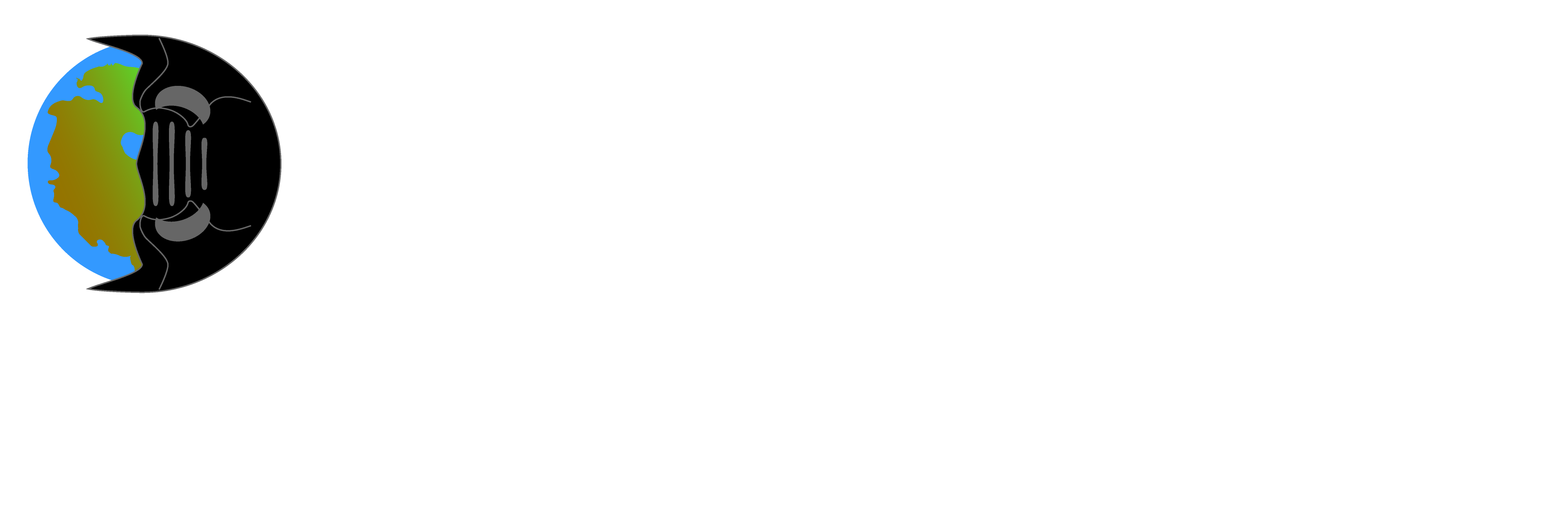

Above Image: Giant barrel sponges (Xestospongia testudinaria). Source: Albert Kok (Wikimedia Commons; Public Domain). Carnivorous sponge of the family Cladorhizidae. Source: NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program (Public Domain). Yellow tube sponge. Source: Julie Bedford, NOAA affiliate (Public Domain).

Class Demospongiae Snapshot

- Examples: bath, tube, barrel, carnivorous sponges, etc.

- Ecology: marine and freshwater

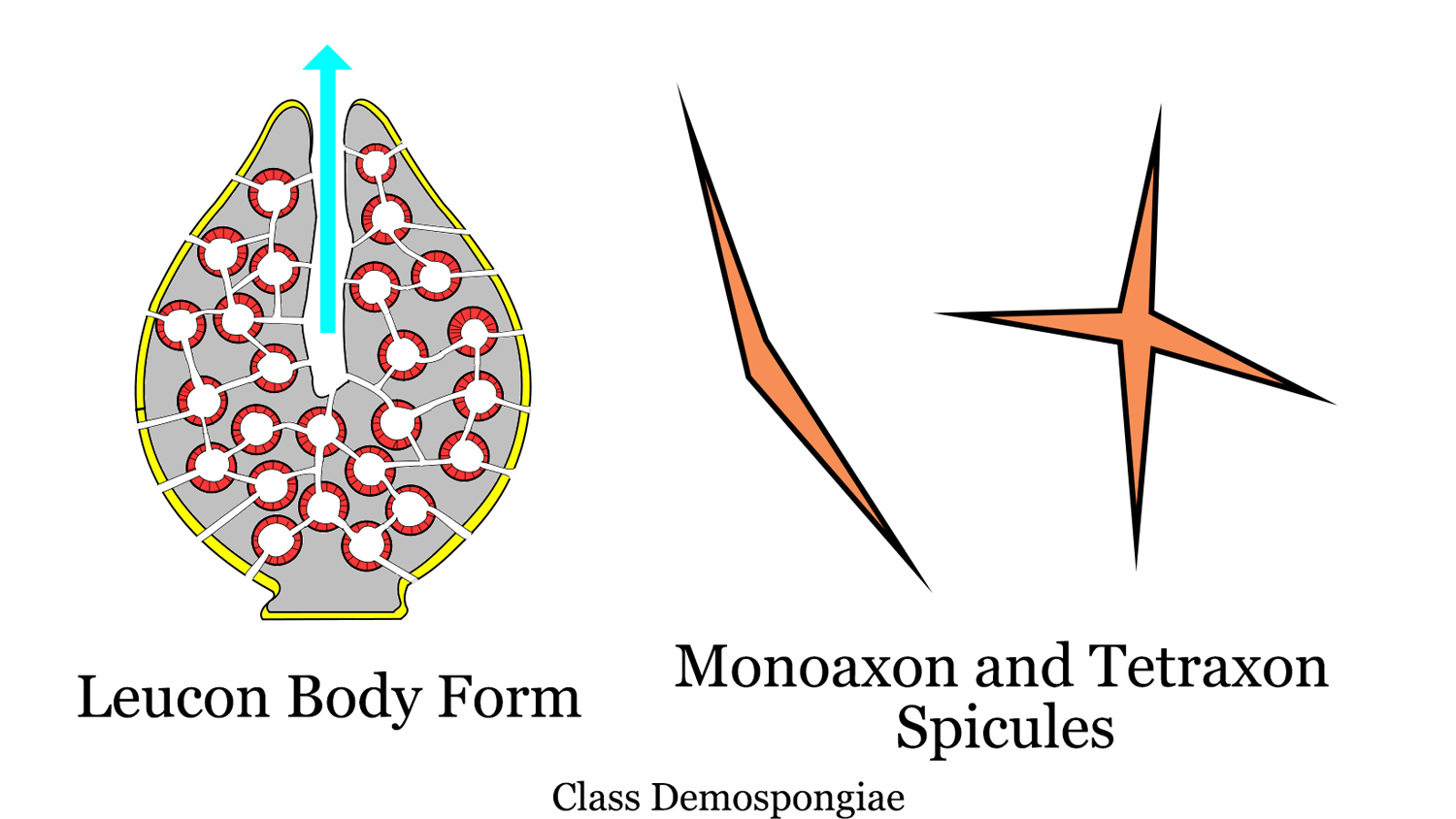

- Key features of group: leucon body form, monoaxon or tetraxon spicules

- Diversity: 7646 living sp., over 90% of all living sponges

- Fossil record: Cambrian to Recent

Overview

Demospongiae represents the dominant class of living sponges, representing more than 90% of all those alive today. Few demosponges have hard skeletons, leaving behind a sparse fossil record compared to other classes. The clade is, however, very diverse, with over 7000 living species. Many demosponges support other organisms (including sea turtles and angelfish) by being a source of food.

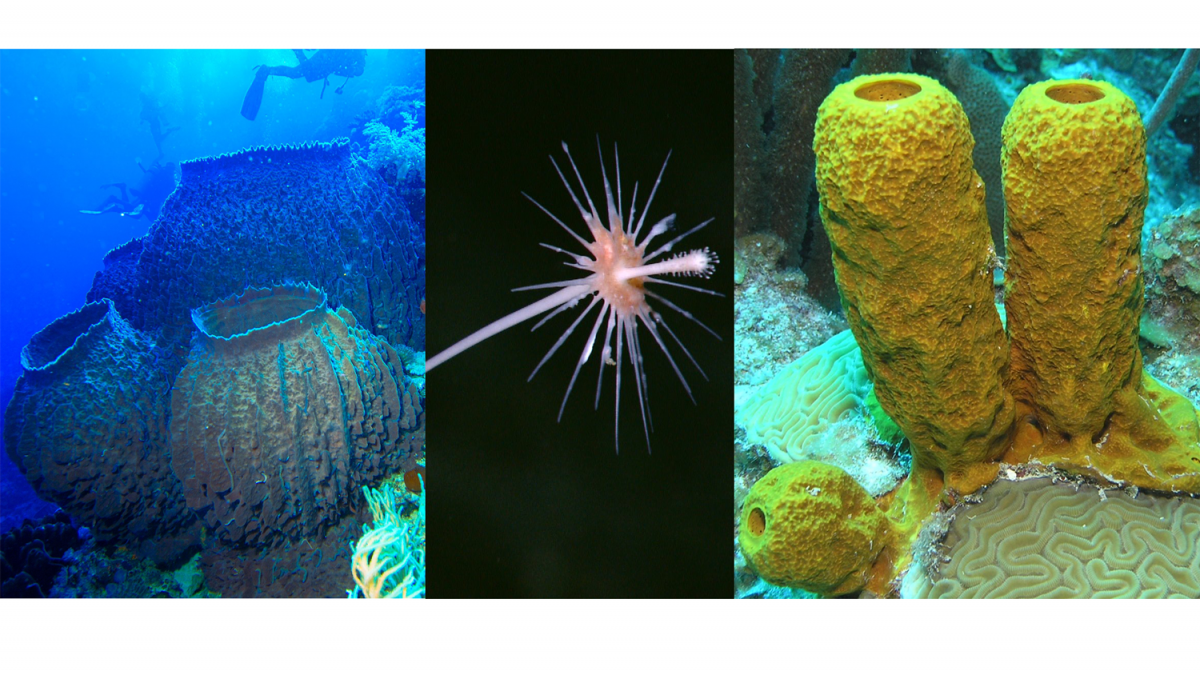

Demosponges have the most complex sponge body form with monoaxon or tetraxon spicules. With the majority of spicules made of silica, this class is included in the major sponge group Silicea.

Highly simplified overview of porifera phylogeny based in part on the hypothesis of relationships presented by Botting and Muir (2018). Image by Jaleigh Q. Pier, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Sponge leucon body plan modified from original image by 'Philcha' (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Public Domain Dedication). Spicule image by Jaleigh Q. Pier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Demospongiae has a long fossil record dating to the Early Cambrian. Fossil demosponges are prevalent in Permian and Cretaceous rocks.

Phanerozoic genus-level diversity of Demospongiae (graph generated using the Paleobiology Database Navigator).

Bath Sponges (Spongidae)

Some sponges lack spicules altogether, creating a soft 'spongy' structure ideal to be used as a cleaning tool. Although our household sponges are manufactured from synthesized materials now, they used to come from natural sponges belonging to the family Spongidae. Spongidae has an affinity for warm waters, where the sponge industry has over exploited them in some regions. The video below shows how natural sponges were once fished for and sold.

"Sponges!" by Jonathan Bird's Blue World (YouTube).

Modern specimen of a soft “bath sponge” (likely Spongia officinalis; locality information is not available). Specimen is from the teaching collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York. Length of specimen is approximately 12 cm.

Boring Sponges (Clionidae)

Not all sponges are boring! (pun intended!) Have you ever seen a seashell on the beach covered in tiny holes? Excavating (or boring) sponges (Clionidae) are likely to blame. This family of sponges use acid to etch out the calcium carbonate of shells and other surfaces to create a home.

Boring sponges (Cliona sp.) Image by Philippe Bourjon (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License).

Modern specimen of the tulip snail Fasciolaria tulipa with numerous small holes created by the boring sponge Cliona celata. These dwelling traces are called Entobia. Specimen is from Florida and is part of the teaching collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York. Length of shell is approximately 10 cm.

Modern specimen of the bivalve Spisula solidissima showing numerous holes made by boring sponges (T-210). These dwelling traces are called Entobia. Specimen is from Cape May County, New Jersey and is part of the teaching collection of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York. Width of clam shell is approximately 12.5 cm.

Fossil specimen of the gastropod Conus yaquensis from the upper Pliocene Tamiami Formation (Pinecrest Beds) of Sarasota County, Florida (PRI 70658). The small holes on the specimen were produced by boring sponges; these types of trace fossils are called Entobia. Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution.

Redwoods of the Reef

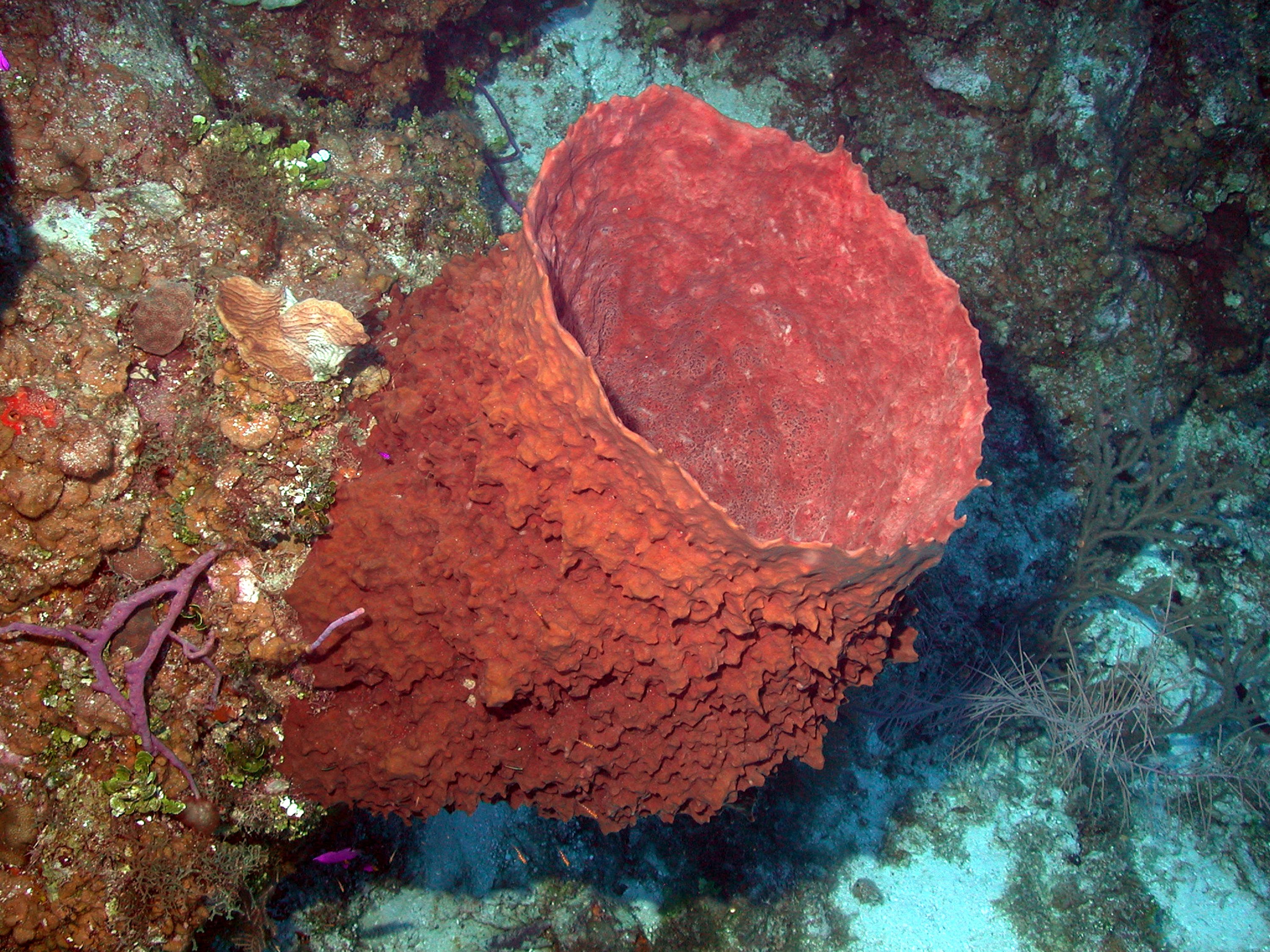

Giant barrel sponges, such as Xestospongia muta, are referred to by some as "Redwoods of the Reef." This group of sponges are known to reach massive sizes and ages of 2000 years or more in warm Caribbean seas (Van Soest, 2012).

Original Caption: "Xestospongia muta, the barrel sponge, may live for 100 years and grow to over 6 feet tall. While populations have declined at sites throughout the Caribbean, they appear to be quite healthy on Little Cayman Island. Caribbean Sea, Cayman Islands." Source: NOAA (Public Domain).

Giant barrel sponges (Xestospongia testudinaria). Source: Albert Kok (Wikimedia Commons; Public Domain).

Freshwater Sponges (Spongillidae)

Freshwater sponges (suborder Spongillina) inhabit virtually every kind of freshwater habitat across every continent except Antarctica. They have been found at depths of hundreds of meters in lakes, to encrusting surface rocks along streams, to swamps and even alpine water bodies. These hardy creatures are everywhere, with the greatest diversity rooted in the Neotropoic and Palaearctic regions. The oldest fossils of this family date back to the Carboniferous, but there has been a boom in diversity since the Eocene (56 million years ago).

Freshwater sponges (Spongilla), on a river bottom in Belarus. Source: Oleg Kirillow (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Public Domain Dedication)

NEWS: Eye Lesion Outbreak in Brazil

Although most sponges are harmless, their sharp spicules can be irritants. In 2005, the Brazilian Ministry of Health called for a multidisciplinary team of researchers when 59 people developed eye lesions after swimming in the Araguaia River in the Tocantins state of Brazil.

Most of the affected were children who experienced itchy, burning sensations in their eyes after swimming in the river and most developed eye lesions a few weeks later. Initially, a water borne disease or parasite was suspected. After a year of intensive research, however, it was determined that freshwater sponge spicules were causing the outbreak. The local area has a known sanitation problem where sewage treatment plants were once being constructed but never finished. During tourist season this becomes an exacerbated problem. An invasive clam species unaffected by these conditions rapidly populated the area, preventing sponge larvae from settling on the river bottom. Without attachment, the larvae disintegrated, causing loose spicules to float in the water and into the eyes of the swimmers (Cruz et al., 2013).

Carnivorous Sponges (Cladorhizidae)

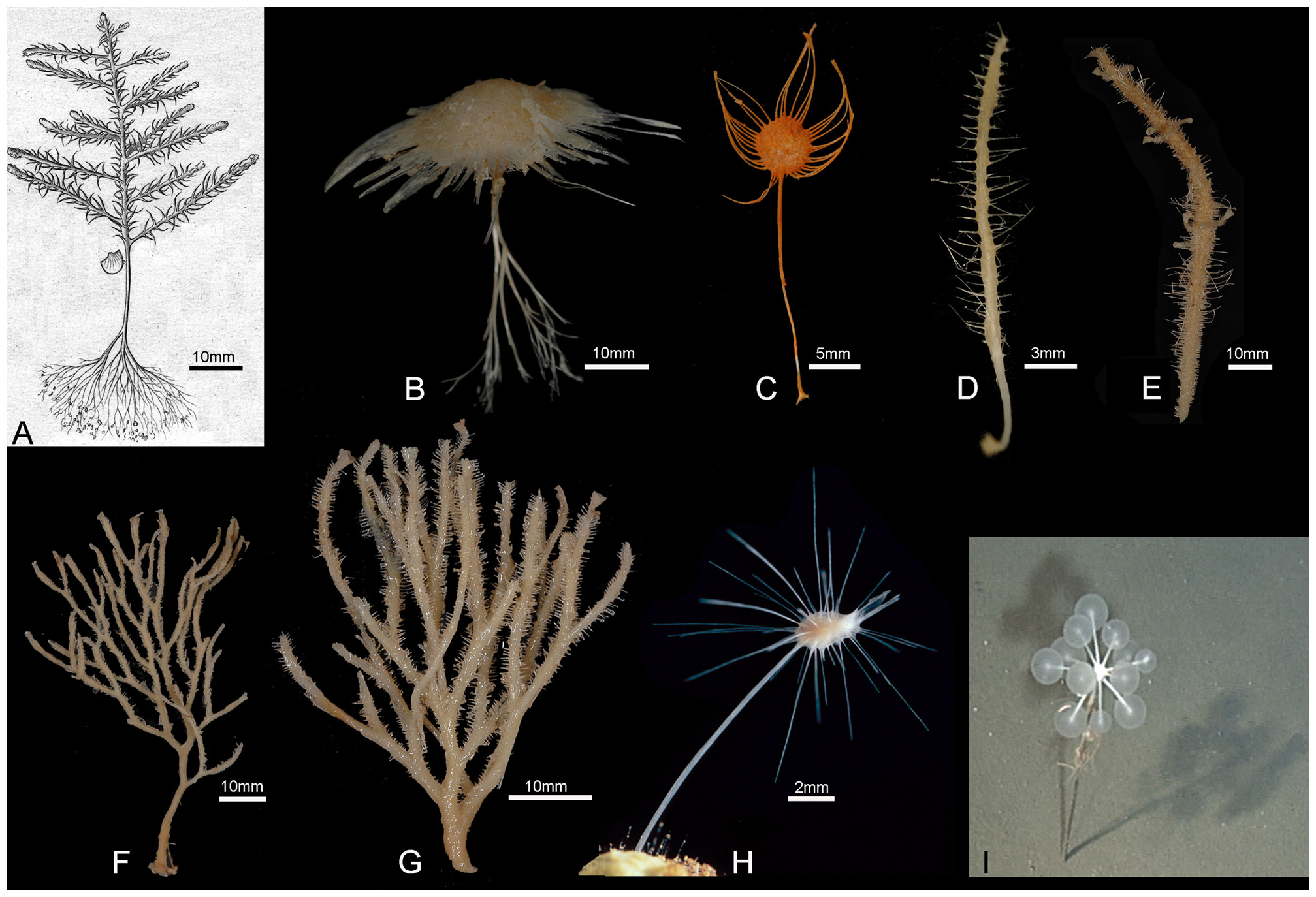

Carnivorous sponges have traded their choanocyte water current system for a sticky outer surface to capture prey. Long hooks act like Velcro, trapping unlucky small invertebrates passing by, which become the sponge's next meal. With no digestive system, individual cells slowly break down the prey at the cellular level. Carnivory seems to be a sponge adaptation to living at great depths, where other particles may be more difficult to come by. Watch the video below to learn about four species of carnivorous sponge!

Carnivorous sponges. A. Cladorhiza abyssicola , scale approximate B. Cladorhiza sp., undescribed species from West Norfolk Ridge (New Zealand EEZ), 757 m (NIWA 25834); C. Abyssocladia sp., undescribed species from Brothers Seamount (New Zealand EEZ), 1336 m (NIWA 21378); D. Abyssocladia sp., undescribed species from Chatham Rise (New Zealand EEZ), 1000 m (NIWA 21337); E. Abyssocladia sp., undescribed species from Seamount 7, Macquarie Ridge (Australian EEZ), 770 m (NIWA 40540); F. Asbestopluma (Asbestopluma) desmophora, holotype QM G331844, from Macquarie Ridge (Australian EEZ), 790 m (from Fig. 5A in [47]); G. Abyssocladia sp., undescribed species from Seamount 8, Macquarie Ridge (Australian EEZ), 501 m (NIWA 52670); H. Asbestopluma hypogea from [41]; I. Chondrocladia lampadiglobus (from Fig. 17A in [48]). Image from (Van Soest et al., 2012) (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic License)

Fossil Demospongiae

Fossil specimen of the demosponge Phymatella sp. from the Upper Cretaceous of Hover, Germany (PRI 70589). Also present is a belemnite with an additional unidentified sponge that may have grown upon it. Specimen is from the research collections of the Paleontological Research Insitution, Ithaca, New York. Phymatella is approximately 4.5 cm in length; belemnite is approximately 6.5 cm in length; sponge attached to belemnite is approximately 4 cm in length

Fossil specimen of the demosponge Hallirhoa costata from the Cretaceous of Wiltshire, England (PRI 76849). Specimen is from the research collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York. Maximum diameter of specimen is approximately 9 cm.

Fossil specimen of the demosponge Verruculina reussi from the Cretaceous of Yorkshire, England (PRI 76847). Specimen is from the research collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York. Maximum diameter of specimen is approximately 9.5 cm.

Fossil specimen of the sponge Hindia sp. from the Devonian Helderberg Group of Schoharie County, New York. Maximum diameter of specimen is approximately 6 cm.

References and further reading:

Bergquist, P.R., and J.H. Bedford. 1978. The incidence of antibacterial activity in marine Demospongiae: Systematic and geographic considerations. Marine Biology, 46: 215-221.

Boardman, R.S., Cheetham, A.H., and Rowell, A.J. 1987. Fossil Invertebrates. Blackwell Scientific Publications. 713 pp.

Botting, J.P, and Muir, L.A. 2018. Early sponge evolution: A review and phylogenetic framework. Palaeoworld: 27, pp. 1-29.

Brusca, R.C., and G.J. Brusca. 2002. Invertebrates Second Edition. Sinauer Associates Inc. Publishers, Sunderland MA. 936 pp.

Cruz, A., Alencar, V., Medina, N. et al. 2013. Dangerous waters: outbreak of eye lesions caused by fresh water sponge spicules. Eye 27, 398–402.

Lundsten, L., Reiswig, H.M., and Austin, W.C. 2014. Four new species of Cladorhizidae (Porifera, Demospongiae, Poecilosclerida) from the Northeast Pacific. Zootaxa 3786 (2): 101-123.

Van Soest, R.W.M., et al. 2012. Global Diversity of Sponges (Porifera). PLoS ONE: 7(4), pp. 1-23.

Usage

Unless otherwise indicated, the written and visual content on this page is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This page was written by Jaleigh Q. Pier. See captions of individual images for attributions. See original source material for licenses associated with video and/or 3D model content.