Chapter contents:

Echinodermata

–– 1. Exclusively Fossil Taxa

–– 2. Crinoidea

–– 3. Asteroidea

–– 4. Ophiuroidea

–– 5. Echinoidea

–– 6. Holothuroidea ←

This page is by Jaleigh Q. Pier and was last updated December 20th, 2019.

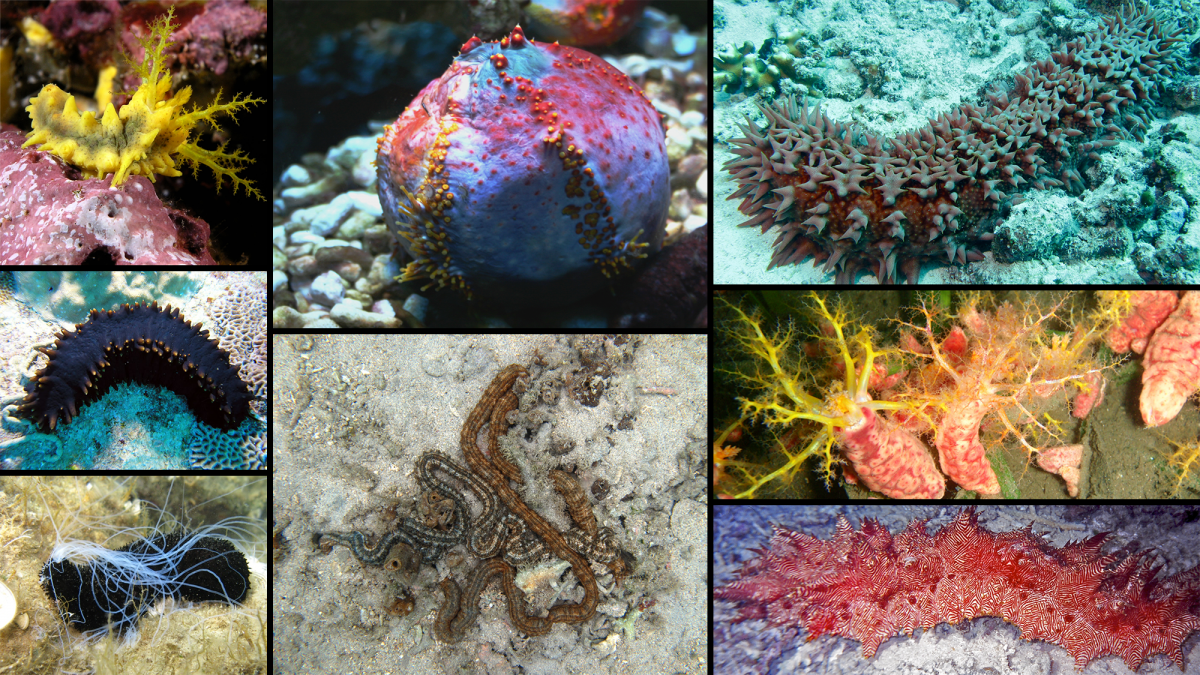

Above Image: Top Left: Yellow sea cucumber by: Nick Hobgood (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License). Center Left: Stichopus chloronotus sea cucumber by: Anders Poulsen (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License). Bottom Left: Holothuria forskali sea cucumber eviscerating cuverian tubules by: Roberto Pillon (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License). Top Center: Paracucumaria tricolor aka the beach ball sea cucumber by: Karel Jakubec (Wikimedia Commons; Public Domain). Bottom Center: Synapta maculata sea cucmbers by: Elisabeth Morcel (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License). Top Right: Thelenota ananas sea cucumber by: Bernard Dupont (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License). Center Right: Cercodemas anceps sea cucumber by: Peter Southwood (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License). Bottom Right: Thelenota rubralineata sea cucumber by: Bernard Dupont (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License).

Class Holothuroidea Snapshot

- Examples: sea cucumbers

- Ecology: marine

- Key features of group: Mobile epifaunal detritivore

- Diversity: 3,933 living sp., 1,336 extinct sp.

- Fossil record: Ordovician to Recent

Overview

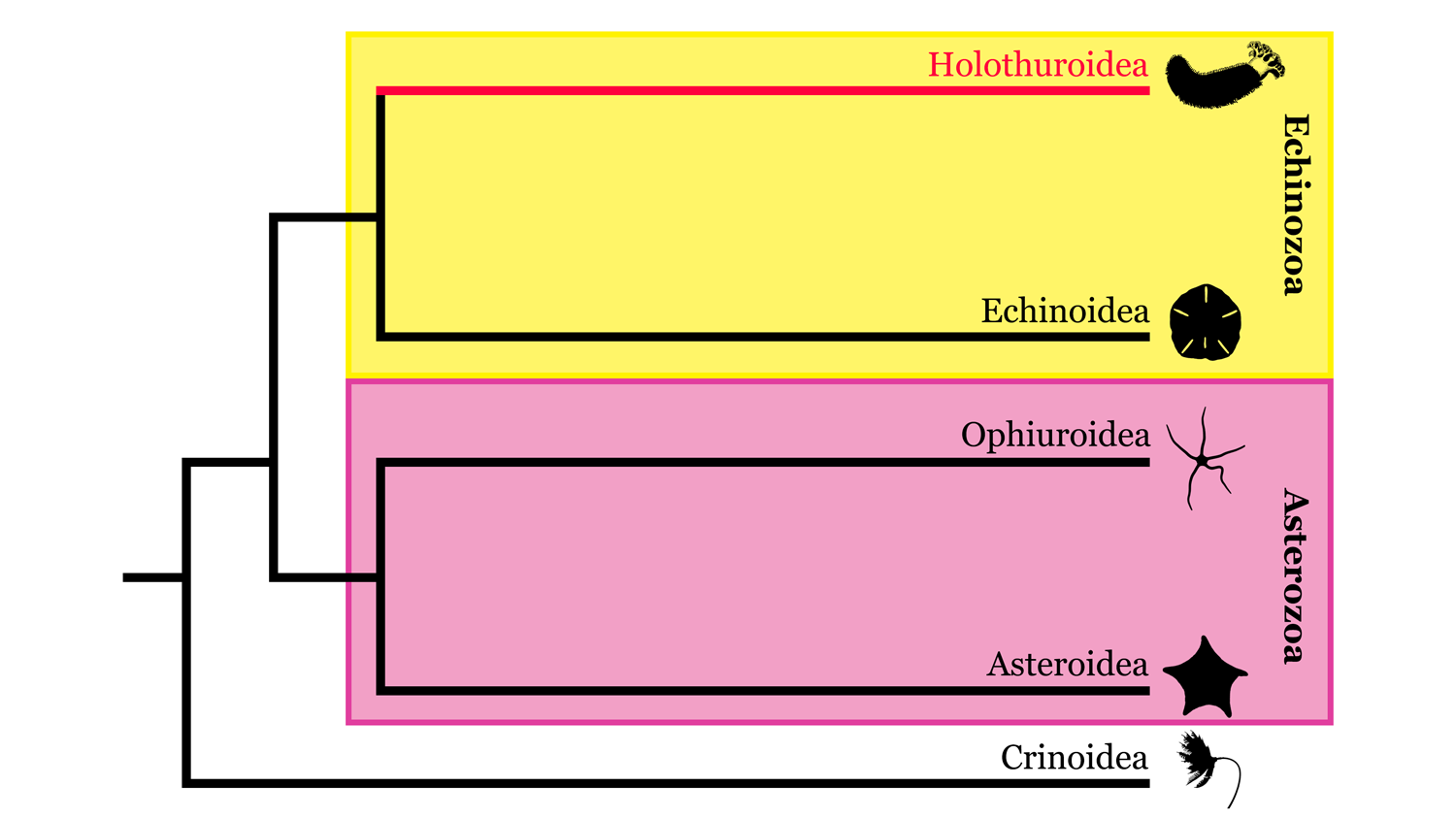

Holothuroideans, or sea cucumbers, appear to have bilateral symmetry in their adult form, but several structural characteristics are still formed in five parts. Class Holothuroidea is a sister clade to class Echinoidea, which together make up the clade Echinozoa.

Highly simplified overview of Echinodermata phylogeny based in part on the hypothesis of relationships presented by Reich et al. (2015). Image by: Jaleigh Q. Pier, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License.

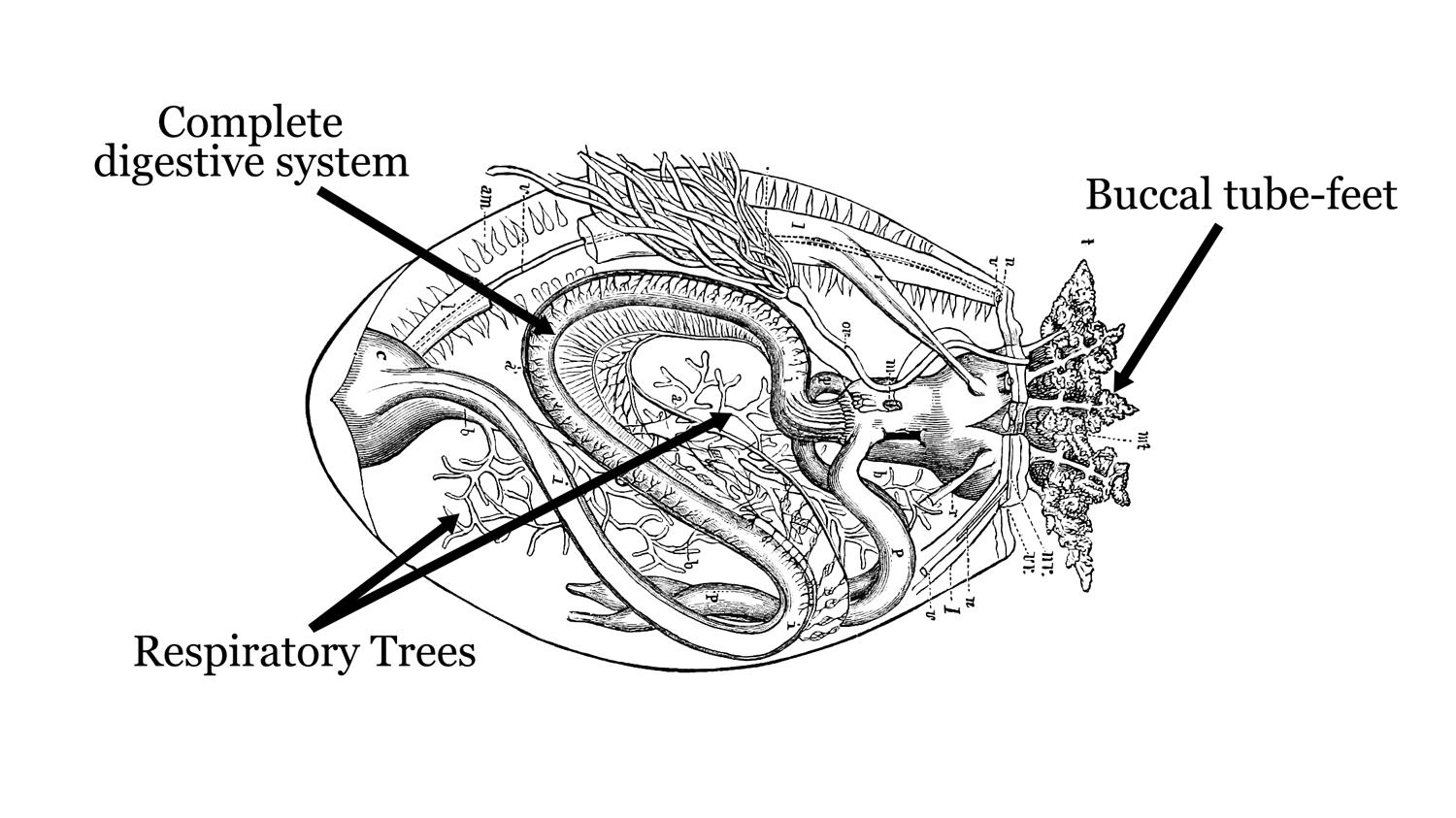

Sea cucumbers are soft, slimy, and almost worm-like, but do have spicules made of calcium carbonate in their tissues; much of their fossil record consists of these small spicules. Sea cucumbers have a complete digestive system with two openings: a mouth and anus. Holothurians are uniquely anal respirators, meaning they breathe through their rear end. They have respiratory trees that act as ‘lungs’ to transfer oxygen into the body and get rid of carbon dioxide. Check out the diagram below to get a better idea of sea cucumber internal anatomy.

Labelled diagram of sea cucumber internal anatomy. Image from "Zoology: for students and general readers " (1879) by: A.S. Packard (Flickr; Public Domain).

Like all echinoderms, sea cucumbers have tube-feet. Most species have feathery, buccal tube-feet that extend from the mouth to help sift detritus from soft sediments. Due to this common feeding behavior and worm-like appearance, they are often called the earthworms of the sea. Commonly it is said that every grain of sand in the ocean has been ingested by a sea cucumber at least once.

But don't let their docile appearance fool you! Sea cucumbers have evolved adaptations in their hundreds of millions of years of evolution that prove they are not to be underestimated. The video below is a general introduction to the class Holothuroidea.

‘Why Sea Cucumbers Are Dangerous’ by Facts in Motion (YouTube)

Tube-feet Specializations

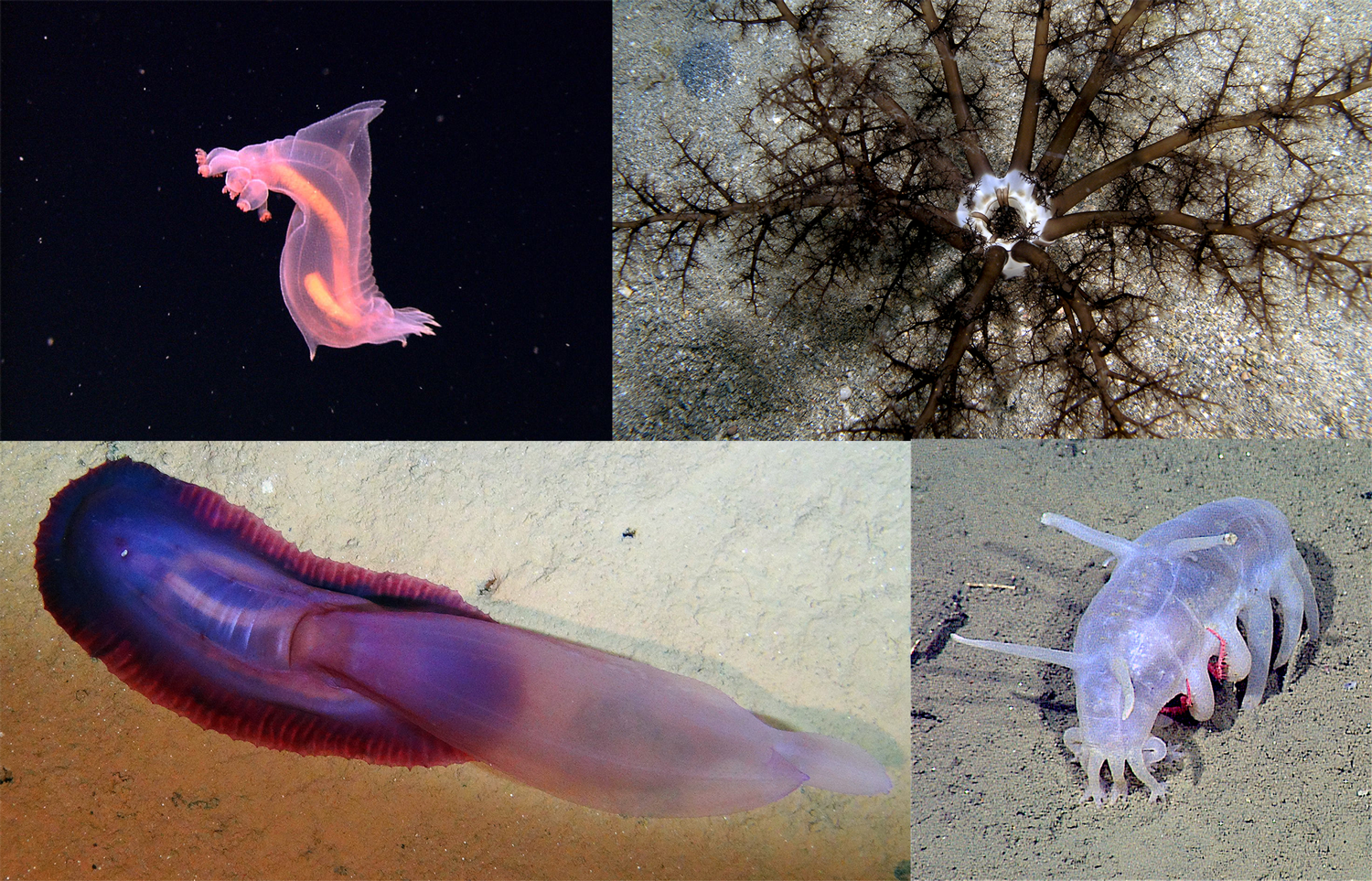

Sea cucumbers are surprisingly elegant and diverse. They have developed several feeding methods: some crawl along the seafloor to sift detritus, others burrow into sediments with their tube-feet exposed to capture particles, some are suspension feeders, and a few even swim and actively capture moving prey such as plankton.

Tube-feet diversity. Top Left: A planktonic sea cucumber. Image by: NOAA Okeanos Explorer (Wikimedia Commons; Public Domain). Top Right: a burrowing sea cucumber. Image by: Nick Hobgood (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License). Bottom Left: Psychropotes semperiana sea cucumber with a sail-shaped tube-foot. Image by: Smith & Amon 2013 (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License). Bottom Right: A sea pig (Scotoplanes globosa). Image by: NOAA (Wikimedia Commons; Public Domain).

Some sea cucumbers have tube feet along the outside of their bodies to help with movement across the ocean bottom or to sense the direction of food. Others have specialized tube feet adapted to swimming or floating within the water column.

Video by: NOAA Okeanos Explorer (Public domain) Start video at 1:33 minutes!

Defense Mechanisms

Being little more than a fleshy mass, sea cucumbers are often sought out as prey by other organisms. There are even a few that target sea cucumbers exclusively as their food source, like the tun snails. The partridge tun (Tonna perdix) uses a mouth full of sulfuric acid to help digest the sea cucumber's body as it swallows them whole (Kropp, 1982).

A partridge tun snail (Tonna perdix) consuming a sea cucumber at night. Image by: Sébastien Vasquez (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License).

Sea cucumbers have evolved a few mechanisms to prevent being predator's next meal. Holothuroidea in Greek means "violent expulsion," referring to their bizarre defense mechanism. When threatened, some species will eviscerate their internal organs, distracting their attacker so they can make a safe getaway. They are then able to regenerate these internal organs. Cuverian tubules in some species are attached to their internal respiratory trees and are used specifically for this purpose. If attacked, the sticky and sometimes toxic threads can distract and entangle predators so they can make an escape. Watch this in action with the video below!

'Sea Cucumber Fights with Guts (Literally)' by National Geographic's World's Weirdest Series (YouTube)

Several species are common in aquaria; however, caretakers must take extreme caution. If provoked, sea cucumbers can release a powerful toxin, called holothurin, into the water, sometimes killing the entire aquarium ecosystem. These toxins are being tested by the pharmaceutical industry for their potential as medicinal treatments.

In many Asian cultures, non-toxic sea cucumbers are a delicacy and have been cultured for more than 1,000 years (Zhou et al., 2016). There is still a high demand for sea cucumbers and a booming aquaculture industry to help support it.

Pearlfish Parasites

Pearlfish are sleek fish that grow to maximum of 20 inches (50 cm) and inhabit the world’s tropical oceans. Pearlfish are parasites. To hide from predators, they search out an unassuming invertebrate host to hide in. The most rude pearlfish live inside the back end (i.e., hindgut) of sea cucumbers and nibble on their innards. Some sea cucumber species have evolved ‘anal teeth’ to prevent this type of parasitism. Watch the BBC video below for more information!

Natural World 2016: Episode 2 Preview by: BBC (YouTube)

The Sea Pig

Scotoplanes globosa is more commonly known as the sea pig. The sea pig was first discovered by the Swedish scientist Hjalmar Théel aboard the HMS Challenger expedition in 1873-1876 and described in 1882. Sea pigs can be found in congregations of tens to hundreds of individuals along the abyssal plain of the deep-sea. In addition to normal tube-feet used for locomotion, they have four sensory tube feet on their backs to help search out food (Hansen, 1967). Watch the video below to get an up-close look!

"We Can’t Tell if the Sea Pig Is Adorable or Terrifying" by: WIRED (YouTube)

Fossil Record

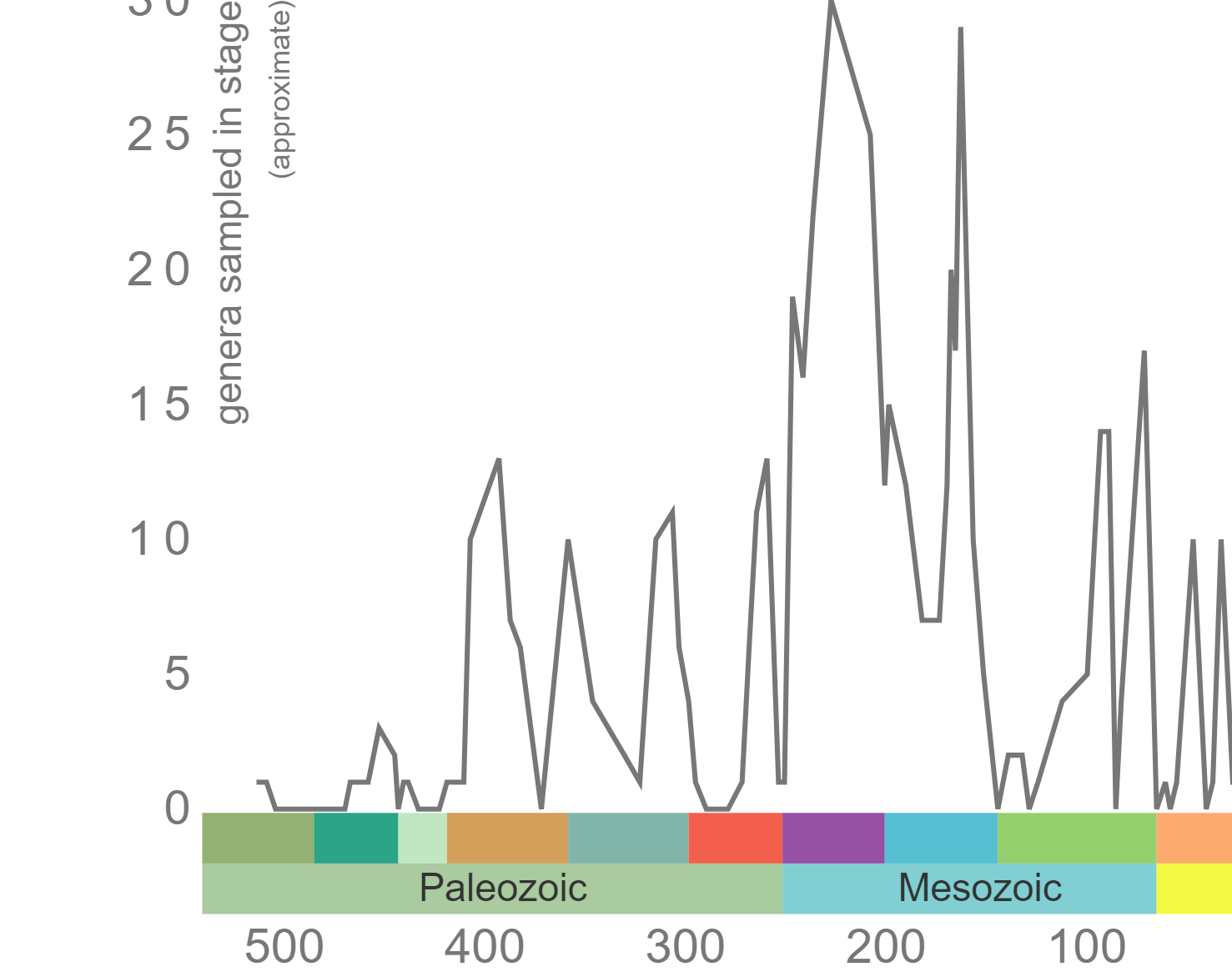

As previously mentioned, sea cucumbers have a very poor fossil record owing to their mostly soft bodies. Body fossils are extremely rare and are known mostly from Lagerstätten deposits.

Achistrum sp. sea cucumber from the Mazon Creek of Illinois with ossicles around mouth preserved. Specimen from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, NY. Image by: Jaleigh Q. Pier, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License.

A Chiridotidae body fossil from the Mazon Creek of Illinois (National Museum of Victoria, P 75336-1). Image by David Bowers (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License).

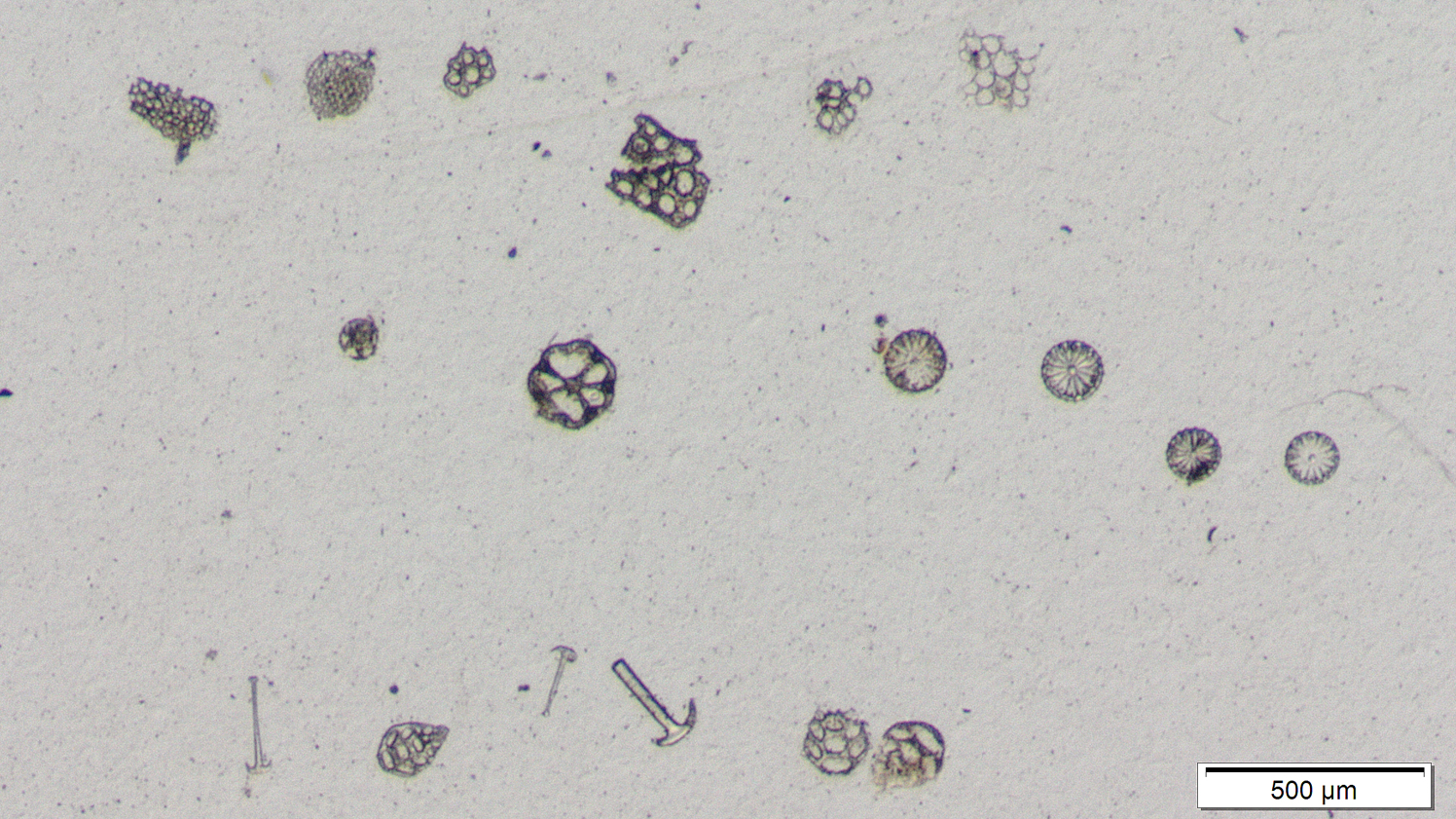

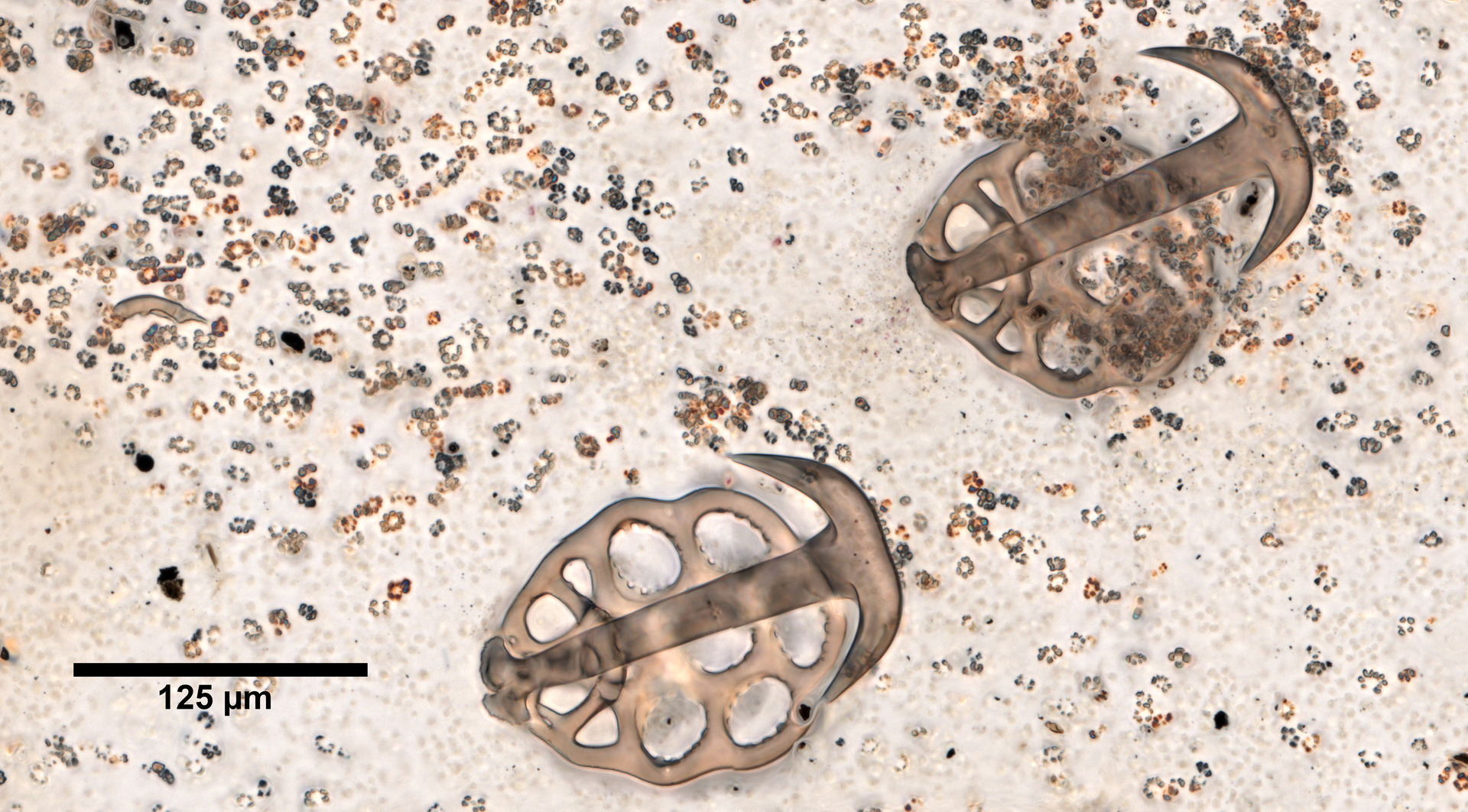

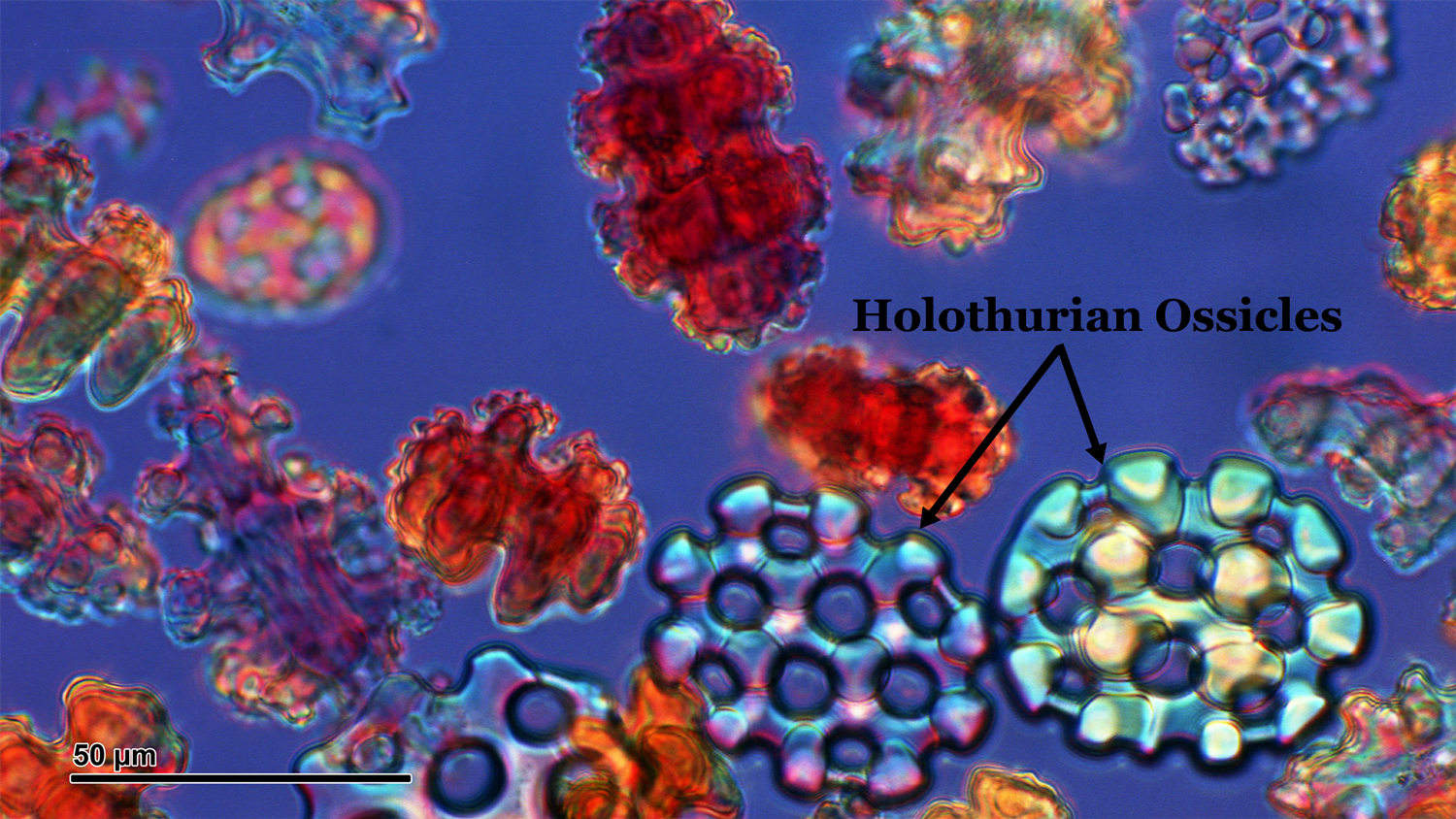

Even though they are mostly soft bodied, sea cucumbers do have calcareous ossicles that may preserve well. Many sea cucumbers have calcareous plates around their mouth to help support their large buccal tube-feet and ossicles embedded in their body wall for support. These ossicles are the basis for recognition of major phylogenetic groups and are known as far back as the Ordovician. Most of the fossil record of sea cucumbers consists of these small structures.

Phanerozoic genus-level diversity of Holothuroidea (graph generated using the Paleobiology Database Navigator).

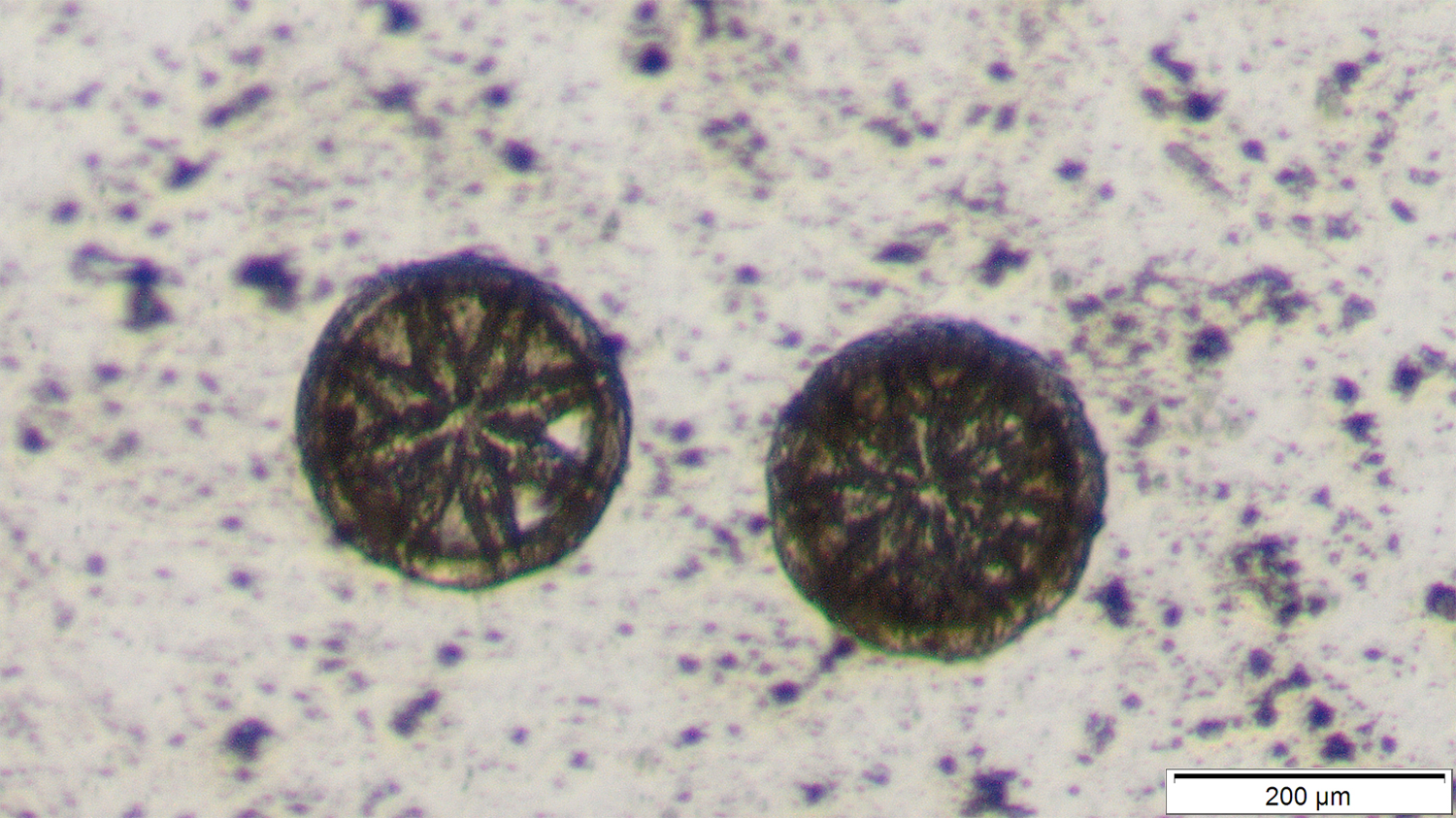

Ossicle forms are very diverse including wheel, anchor, hook, and needle-like shapes. It is estimated that some individuals may have as many as 10-20 million of these tiny ossicles in their bodies (Boardman, 1987 p. 593).

Fossil spicules and ossicles of Hemisphaeranthos costifera from the Eocene of France (MNHN B72409). Specimens part of the collection of the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle (MNHN - Paris) (iDigBio, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License)

Fossil wheel-shaped spicules of Hemisphaeranthos costifera from the Jurassic of France (MNHN B08673). Specimens part of the collection of the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle (MNHN - Paris) (iDigBio, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License)

Anchor-shaped spicules of Synapta sp. (YPM IZ 077070). Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History; photo by Daniel J. Drew 2015 (iDigBio, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 1.0 Public Domain Dedication)

A mix of sponge, coral, and sea cucumber ossicles. Image by: Josef Reischig (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License)

References and further reading:

Boardman, R.S., Cheetham, A.H., and Rowell, A.J. 1987. Fossil Invertebrates. Blackwell Scientific Publications. 713 pp.

Hansen, B. (1967). The taxonomy and zoogeography of the deep-sea holothurians in their evolutionary aspects. Stud. trop. Oceanogr. 5: 480-501

Igor Yu. Dolmatov, “Asexual Reproduction in Holothurians,” The Scientific World Journal, vol. 2014, Article ID 527234, 13 pages, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/527234

Kropp, R.K., 1982. Responses of Five Holothurian Species to Attacks by a Predatory Gastropod, Tonna perdix. Pacific Science, 36(4), p. 445-452.

Nichols, D., 1967. Echinoderms. Hutchinson University Library, London.

Reich, M. (2010). The oldest synallactid sea cucumber (Echinodermata: Holothuroidea: Aspidochirotida). Paläontol Z , 84: 541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12542-010-0067-8

WoRMS (2019). Scotoplanes globosa (Théel, 1879). Accessed at: http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=148773 on 2019-12-10

Zhou X, Cui J, Liu S, Kong D, Sun H, Gu C, Wang H, Qiu X, Chang Y, Liu Z, Wang X. 2016. Comparative transcriptome analysis of papilla and skin in the sea cucumber, Apostichopus japonicus. PeerJ 4:e1779 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1779

Usage

Unless otherwise indicated, the written and visual content on this page is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This page was written by Jaleigh Q. Pier. See captions of individual images for attributions. See original source material for licenses associated with video and/or 3D model content.